Benevolence and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed.

“Benevolence”—this is Aaron; “truth”—this is Moses. “Righteousness” is Moses; “peace” is Aaron.

Midrash Rabbah

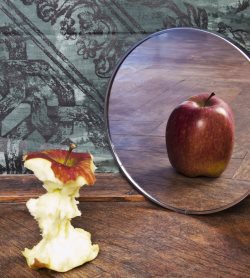

Can Truth and Benevolence indeed meet? Where and how do Righteousness and Peace converge? Do not Moses and Aaron represent intrinsically incompatible realities?

Truth is resolutely objective, while benevolence is gloriously subjective. Peace advocates compromise, which is anathema to rightness. Yet for forty years Moses and Aaron jointly led the people of Israel. The Torah (which freely reports on the negative occurrences within the Israelite camp, including failings on the part of both Moses and Aaron), describes the relationship between the brothers as one of mutual regard and unflagging harmony. In the formative period between their exodus from Egypt and their entry into the Land of Israel, the people of Israel were guided by a leader who conveyed to them the absolute, immutable truth of the divine wisdom and will, and simultaneously led by one who empathized with their human equivocality, and was a master peacemaker and compromiser, resolving conflicts “between a man and his fellow and a man and his wife.”

To understand the relationship between Moses and Aaron, we must examine the single instance in which their respective modes of leadership did come into conflict. For the Torah records one occasion on which the brothers were in disagreement—a disagreement in which Moses was provoked to anger, but then conceded to Aaron.

The Uneaten Offering

It was first of Nissan of the year 2449 from Creation (1312 BCE), two weeks before the first anniversary of the Exodus—the day on which the Sanctuary was erected and dedicated. Actually, the Sanctuary had already been in operation for seven days, but these were “training” days, in which Aaron and his sons were initiated into the priesthood. It was on this, the eighth day, that Aaron assumed his role as kohen gadol (high priest), and the manifest presence of G‑d (the Shechinah) came to dwell in the Sanctuary.

But then tragedy struck. Aaron’s two elder sons, Nadav and Avihu, “offered strange fire before G‑d, which G‑d had not commanded. A fire came forth from before G‑d and consumed them, and they died before G‑d” (Leviticus 10:1–2). G‑d commanded that the dedication of the Sanctuary should not be disrupted. Although Aaron and his two remaining sons now had the status of first-day mourners (onenim), who are ordinarily forbidden to eat the holy meat of the offerings, they were expressly commanded to partake of the special offerings which were brought that day for the dedication of the Sanctuary.

This Aaron, Elazar and Itamar did. But there was also another offering brought that day, one that was not connected with the dedication per se. This was the goat which is brought on the first of every month as a sin-offering. It was over this offering that Moses and Aaron had their disagreement.

Moses saw that the flesh of the goat had been burned, as the law mandates should be done with an offering which for whatever reason cannot be eaten. He angrily demanded why it wasn’t eaten as G‑d had commanded concerning the other sacrifices.

Aaron explained that he had drawn a distinction between kodshei shaah, offerings which G‑d commands to bring on a one-time basis under special circumstances, and kodshei dorot, regularly scheduled offerings which apply equally to all generations. If G‑d commanded something concerning the one-time offerings brought for the Sanctuary’s dedication, argued Aaron, one should not deduce that the same is to apply to the monthly sin-offering. Here the regular laws, which forbid its consumption by a mourner, should apply.

Moses listened to Aaron’s argument and conceded that he was right. He freely admitted that the distinction had escaped him, and that Aaron had concluded correctly.

Absolutism and Vicissitude

Here we have the confrontation between Truth and Benevolence, between Righteousness on the one hand and Peace on the other. Moses, as transmitter of Torah—truth par excellence—saw no reason to distinguish between kodshei shaah and kodshei dorot, between something that is a product of the specialty of the moment and that which is routine in man’s service of G‑d. What is true and right is always true and right, regardless of the circumstances.

Aaron, on the other hand, was the high priest of Israel, the very embodiment of a people’s striving to come close to and serve their G‑d. He understood that man’s service of G‑d is an offering of the sum total of what man possesses, a giving of the utmost of his or her subjective self. He appreciated that there are up and downs in the life of man, and that which is expected of him in his finest, most inspired hours does not necessarily apply to his routine, everyday self.

Hence the conflict. On one side stands Moses, conveying the divine truth and will—a truth and will as unequivocal as their conceiver. On the other side stands Aaron, leading a people’s endeavor to approach that very truth and that very will with the tools of their human selves—a subjective mind with which to seek, an equivocal heart with which to feel, and actions subject to the circumstances under which they are undertaken.

And what happens? Moses agrees with Aaron! Absolute truth grants legitimacy to the “sub-truths” of a relative world.

Indeed, what did happen? How has this seemingly irresolvable contradiction been resolved?

Points of Contact

What happened was that Moses gained a deeper understanding into the nature of truth.

When contemplating and discussing our own, decidedly subjective, reality, we freely use the adjective “truth.” We speak of our “true feelings” and our “true desires”; we claim to “truly understand” something, or to have discovered “the true facts” surrounding a certain occurrence. But if we define “truth” as a reality that is absolute and unequivocal, it would seem that the term could be correctly applied to only to the consummate truth of the divine. Are all applications of term to our circumstantial reality nothing more than self-deceptions?

Chassidic teaching says not. Indeed, the prophet (Jeremiah 10:10) proclaims, “G‑d is truth”; but the chassidic masters understand this to mean not only that G‑d is the essence of truth, but also that He is the source of all that goes by the name of “truth” in our world. His truth is absolute; all other “truths” are relative, with no inherent reality other than that which He chooses to grant them. But it is He who created these subjective realities, and in doing so, He has imparted a legitimacy and truth to their existence. So, if we find relative truths in His creation, these are expressions (albeit imperfect expressions) of His all-pervading truth—-as manifested within the bounds of the many “worlds” or realities which He has created.

In other words, when a person gives it his “all,” his ultimate, he attains a personal absolute—something which, within the context of his subjective personal world, is true. And all truth, including such subjective truths, are expressions of a deeper truth that is their source and empowerer—the truth of their Creator. So, his personal truth touches the truth of G‑d.

This is the joint legacy of Moses and Aaron: that we must strive towards the truth, guided by the directives of Torah and utilizing the talents and resources which we have been granted. We need not be dissuaded from our quest by the finitude of our understanding, the subjectivity of our feelings and the circumstantiality of our deeds. If our efforts are true—albeit “true” only within the context of our relative existence—then “Moses” will concede to “Aaron” that this truth is part and parcel of the Absolute Truth toward which we strive.

Join the Discussion