On Chanukah after sundown, says the Talmud, the menorah is to be kindled outside the door of one’s home. In a time of danger, however, placing it inside one’s home is sufficient.1

For the Rebbe, the Menorah and it’s laws symbolized the ideal role religion should play in the public square, and the religious advantages of democratic emancipation. Judaism should not be a private affair, but a source of moral illumination extending to the darkest corners of society.2 Unlike in places where religion is persecuted, the United States provides a framework where Chanukah, and religion generally, can be celebrated in a way that is “ideal” rather than merely “sufficient.”3

In 1974 these ideas inspired Chabad representative Rabbi Abraham Shemtov to erect the first public Menorah in front of Philadelphia's iconic Liberty Bell. The next year Rabbi Chaim Drizin erected a “giant” Menorah in San Francisco’s Union Square, and within a few years Chabad representatives across the United States and the world were following suit.

Chabad’s public Menorah campaign sparked an exchange of letters between the Rebbe and Joseph B. Glaser, executive vice president of the association of Reform rabbis. Such public expressions of faith, Glaser argued, were not only unconstitutional but also threatened Jews in the public sphere with the influence of religions other than their own. In response the Rebbe reminded him that United States currency bears the motto “in G‑d we trust” and that the pledge of allegiance declares America to be “one nation under G‑d.”4 Faith is not a threat to constitutional liberty but its foundation.5

In 1989 the debate was brought before the United States Supreme Court. The court’s conclusion supported the argument that the constitutional separation of religion and state was not designed to inhibit expressions of religious diversity, but rather to protect them.6

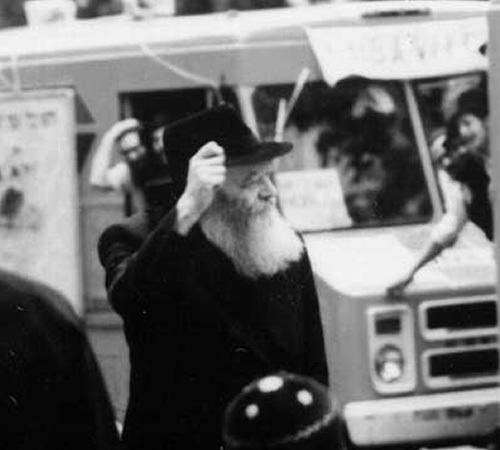

1974 also saw the debut of the Mitzvah Tank on the streets of New York. The Rebbe’s repeated calls for the exponential increase of mitzvah observance among all Jews inspired Yeshiva student Sholom Duchman to outfit trucks to carry Judaism to the streets of Manhattan. The Rebbe was quick to applaud the initiative, and referred to the trucks as “tanks against assimilation.”7 Soon Newsweek was reporting on Chabad’s “cavalcade of vans... seeking parking places on the busiest street corners… Earnest young men with flowing beards emerge… and as they take positions around the vans, loudspeakers on board start to play Hasidic folk music.”8

If a large part of American Jewry no longer came to the synagogue to practice mitzvot and learn about Judaism, the Rebbe was sending his students to bring Judaism to Jews on city sidewalks. Women are offered free kits containing a small candle, and a brochure with all the information necessary to light Shabbat Candles on Friday evening at the proper time (18 minutes before sunset). Men are invited to step up on the truck, roll up their left sleeve, bind tefillin on their arm and head, and recite a short prayer. Information and assistance regarding all aspects of Torah learning, mitzvah observance and Jewish education is offered to every passerby.

Initially a New York phenomenon, it wasn’t long before Mitzvah tanks were in use in other cities too, especially in the Land of Israel. During the 1982 Lebanon War, Mitzvah Tanks accompanied Israel Defence Force units all the way to Beirut, providing vital moral support to frontline troops.9

As with public menorahs, the boldness of this initiative raised a storm of criticism. What is the significance, people asked, of a one time encounter in the street? How could such transience support the eternal perpetuation of Jewish life? Such arguments, the Rebbe responded, betray a total misunderstanding of the nature of mitzvot. Even if you don’t understand the mystical significance of the action, a single mitzvah creates a bond between man and G‑d that utterly transcends the bounds of time.10 A single positive action carries eternal value, and its infinite power can tip the scale of good and evil, bringing enlightenment and redemption to the entire world.11

Both the Mitzvah tanks and the Menorahs brought Jewish observances to the fore of public consciousness in a very visible way. Some Jews felt threatened and embarrassed by such publicity. But the sincere warmth and non-confrontational enthusiasm so openly shared by Chabad chassidim, continues to embolden Jews everywhere to engage more deeply with their Judaism. As the Rebbe put it in one letter to Glaser, “countless Jews… have been impressed and inspired by the spirit of Chanukah which has been brought to them, many for the first time.” It was precisely the open celebration of Judaism that these campaigns embodied that made them so powerful.12

Join the Discussion