I always knew that the Rebbe supported and encouraged artistic achievement, and on a number of occasions, he expressed his feeling that the gift of artistic talent is on the highest level. It is well known that he spent some years as a young man in France while studying engineering at the Sorbonne, and I often imagined that occasionally he might have visited the magnificent Louvre and other museums, as other Rebbeim had done in their time.

When the Crown Heights Art Institute, called the Chai Gallery, opened in Crown Heights, the Rebbe personally issued a check for $10,000, to help with the expenses. The Rebbe instructed that the gallery be used for art instruction, and designated Henoch Lieberman, one of the most gifted Chassidic artists of the century, to conduct classes for both men and women.

The Rebbe also personally attended occasional art exhibitions to indicate his interest in aiding the development of new Jewish artists.

The Rebbe met with hundreds of world leaders and gifted people from many walks of life, among them the famous sculptor Jacques Lipshitz, the creator of Kinetic art; Yakov Agam; and the extraordinary artist from Hebron, Baruch Nachshon.

Earliest Encounters

My relationship with the Rebbe began when I was 15 years old. I then had the privilege of visiting the Rebbe, twice a month, in his study at 770 Eastern Parkway, to receive his instructions about illustrating “Talks and Tales,” the monthly children’s magazine he had initiated.

The Rebbe was then secretary to his father-in-law, the then Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, who had placed him in charge of Lubavitch publications. Under his dynamic leadership, Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch became the largest and most prolific publisher of Jewish books and periodicals, reaching out to Jews all over the world.

The Rebbe wanted to introduce a new feature in “Talks and Tales,” an illustrated page with 5 or 6 items, little known facts about Jewish customs, lore and legend, which would add a new dimension to the publication. The Rebbe wanted this feature to be something that the children would look forward to reading from issue to issue. It was to be titled, “Curiosity Corner.”

Originally, most of Rabbi Schneerson’s ideas were dealt with by his secretary, Rabbi Nissan Mindel. However, very early on, Rabbi Mindel said to me, “Look, why should I be the go-between person, getting the information from Rabbi Schneerson, conveying it to you, then after you draft the necessary sketches based on this information, I bring it in to Rabbi Schneerson for critical commentary, then deliver his comments and corrections to you, to produce the finished artwork and associated copy? It makes more sense to introduce you to Rabbi Schneerson and let you deal directly with him.” And so it came to pass.

As a youngster of 15, I was quite excited at the prospect of such direct face-to-face communication with this great teacher, the son-in-law of the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn.

Rabbi Nissan Mindel ushered me into the office of Rabbi Schneerson, who was standing at his voluminous bookcase reading, deep in thought. We stood there, until he partially turned to me, smiling, and motioned with his right hand for me to have a seat.

I will never forget this awesome scene, his sparkling blue eyes and welcome smile... without uttering a word. I’m sure I was too young to appreciate the significance of the moment, that I was being invited, by the man who was later to become the greatest of all Rebbes, to execute under his tutelage, some of the earliest pictorial interpretations of Judaism for Lubavitch children’s books.

I remember that he thanked me for coming and indicated that he was pleased with my work. He discussed his desire to develop many additional programs for children which he thought I could illustrate for him.

Illustration, in the Rebbe’s view, was a key factor in translating to children the visual essence of the written word. Through pictures which would accompany the text, children would more easily relate to the information that the text was presenting.

He was firmly in favor of producing this work in Yiddish and English. However, since the texts would be different from each other, they would require separate illustrations. As I understood it, the Rebbe felt that even if a child could not read Yiddish, he or she would ask parents or teachers to read and explain what the pictures were about.

When describing the feature, the Rebbe said, “It should look like Ripley, — Es zol oys’zehn vee Ripley.” I was taken by surprise.

For many years, in many newspapers throughout the country, a square measuring approximately 5”x 5”, contained the work of Robert Ripley, titled “Believe It Or Not.” Here was this venerable Rabbi aware of a column, which appeared daily in “The New York Mirror,” now a defunct Hearst publication, asking me to make our feature in Ripley’s style.

On another occasion, the Rebbe asked me to create a true to life character about whom adventure stories could be written. This time he suggested that the format and look should be “like Dick Tracy!”

I created the cartoon, but with the passage of time, totally forgot what it was like. I only remembered vividly that the Rebbe had wanted something to “look like Dick Tracy.” I kept hearing his words, “Ess zul oys’zehn vee Dick Tracy.”

Then, one day after some 40 years, I stopped in at the Lubavitch Book Store on Eastern Parkway and Kingston Avenue and, lo and behold, I was shown a book which contained a feature, in a comic-book format, called “Pee-Wee Meyers.” It was about a Jewish major-league baseball star. This was during the War, and at that time the Brooklyn Dodgers had a truly great star called, “Pee-Wee” Reese.

Sure enough, that was it. And the art was fashioned after the most popular comic strip of that time, Dick Tracy.

Each segment was first discussed with the Rebbe - he had definite input – after which I would write the script, box by box, and prepare pencil sketches of the scenes with balloons for the text. The Rebbe would review each scene or representation, and only after I had his corrections and approval, did I do the finished art, which then went to printer.

The Merkos Logo

In 1944, I was asked to design an emblem for the Rebbe’s publishing division, “Merkos L’inyonei Chinuch’, the Center of Educational Materials and Publications.

I submitted a sketch which showed the world globe in 2 halves super- imposed by the “Tablets of the 10 Commandments.” The copy around the perimeter of the design was hand-lettered in Hebrew and English, in modern face, which the Rebbe always preferred. The overall design itself was, for those days considered Avant-garde, as most all seals for Jewish and other institutions were ornately designed in French and Old English thematics. The Rebbe always supported modern trends in design and publication, similar to the more advanced publishers of the times.

When I presented the new Merkos design, his comment was favorable as to the shape and design. In general, however, he said that the Luchot, the Tablets, were not to be drawn with half-round cupolas at the top of each tablet. The correct design was to draw two vertical rectangles, with a ration of 1 to 1½, flat at the top as well as the base.

The familiar rounded top was introduced by Roman order, derived from their architectural style, prevalent at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Holy Temple. The Roman desire to eradicate everything Jewish, included even the shapes of our most holy symbols.

From that day on, I never again drew the “Ten Commandments” with the “Roman” shape at their top. How I always wished that Jewish artists and architects of synagogues and temples would realize that the perpetuation of a mistake is unacceptable, no matter how long the error has been practiced.

The Map of the Exodus

One Sunday evening in August (1994), I received a call from a Rabbi who said he was writing a book on the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. He was doing much of his research in the Rebbe’s library at 770 Eastern Parkway, and seemed to be having a problem.

“How can I help you?” I asked. “Exodus research is not exactly my field.”

“Yes,” he said, “except that in doing my research on the route taken by the Jews to get through the desert and on into Canaan, I came across a map which shows the route going North up the coastline to Ashkelon, then going East to the Holy Land.”

“Still, where do I fit in to this scenario?” I asked.

“Well, at the bottom of this map is your signature, ‘Michel,’ and the date, 1943.”

“Oh, yes,” I said. “I remember doing a number of maps and charts for the Rebbe. The Exodus route was in one of them.”

“But,” he says, “the problem I have is that so far, in all the books written of the subject, the Israelites took a different route all together. I have almost completed my work, and now I came across your map.”

I really felt sorry for this author, but all I could tell him was, “Look, you may have a problem, and I can appreciate your predicament. The Exodus chart was one of the earliest experiences I had with the Rebbe, and in those days, I did what the Rebbe instructed me to do. I’m no authority on the Exodus. I’m sorry I can’t be of more help.”

I never did find out how he extricated himself from this dilemma.

Tzivos Hashem

It was during Sukkot 1980, that the Rebbe, of righteous memory, spoke of organizing a youth movement, enrolling children of school ages, as “guardians” of G‑d’s commandments. In his infinite wisdom and his extremely practical understanding of the preferences of contemporary youth, he put forth his vision of tens of thousands of Jewish children worldwide, who would “join the army of G‑d,” and begin moving up the ranks from private to general, as they performed Mitzvot (good deeds) and acts of kindness.

The idea was immediately put into practice. On Shabbat, the Rebbe spoke about his new idea, and as soon as the Sabbath was over, several young Chabad men were called upon to get the ball rolling. It was felt that it would be appropriate to have a banner with a suitable ‘military’ emblem for the organization.

“Go see Schwartz,” the Rebbe said. “He will make it for you.”

Now, this was Saturday evening. At about ten o’ clock, I heard the front door chime announcing the arrival of two of my Lubavitch friends, Rabbi Yossi Raichick and Rabbi Mendel Kotlarsky.

After describing the details of what the Rebbe had discussed earlier that day, they informed me that the Rebbe was waiting for their return to see a sketch of the emblem, so that they could go to press on Sunday with flyer, brochures, patches and stickers to launch Tzivos Hashem.

I listened in total amazement. I was being asked to put aside whatever I might have been working on to “help get the ball rolling.” I realized that these wonderful young men were serious, and had no reservations about how I would create a “military” motif. They were sure that the Rebbe would approve. He was awaiting them to come back. They promised to return to me as soon as the Rebbe made his “corrections.”

Without hesitation, I started a Heraldic chevron with 5 ramparts which bore the initials Tzadik - ?, Heh - ?, for Tzivos Hashem, with the words in Hebrew across the face panel.

The initials Tzadik, Heh, were divided by a diagonal, each letter having its own background. The background for the Tzadik was blue with stars and a moon, signifying night; while the Heh had a red sun on a yellow field, signifying day. The Army of G‑d performs Mitzvot day and night all year long.

The messengers Kotlarsky and Raichik snapped up my rather rough sketch, and off they went to see the Rebbe. The time was already past 11:00 P.M.

At approximately 1:00 A.M., they returned all excited, relating the Rebbe’s comments:

“1. Generally he was pleased with shape, the lettering and the format.

“2. He said that Michel should remove the moon & stars from the ‘tzaddik’ background, as this was idol worship. Solid blue would do.

“3. The sun with its red rays behind the ‘hey’ recalled the flag of Japan. Solid red would do very well.

“If I could make these few changes, they would return to the Rebbe, and barring any additional changes, would immediately go to press.”

I revised the rough sketch as the Rebbe suggested, and saw that once again, he was absolutely right. It really looked better, and would be more easily reproduced, even in very small sizes.

I told them that if necessary I would stay up as long necessary, to have the finished art “camera ready” for shooting in the morning.

I never heard from them again that evening. The next day the presses were rolling, reproducing my rough sketch. Not long after that, the motto of Tzivos Hashem, “We Want Moshiach Now!” was added to the emblem, with the Rebbe’s approval. That symbol was used for over 10 years, until I insisted that it was time that they have a piece of finished art for all future reproduction.

Today the Tzivos Hashem emblem is the single most reproduced Jewish organizational symbol in history. Estimates run into the hundreds of millions over the years.

In 1989, a further set of designs were created for the various ranks of ‘soldiers’ in Tzivos Hashem. These were also submitted to the Rebbe for comments and approval. One of the designs, featured the square “Luchot,” but this received the Rebbe’s disapproval. He wrote that the Luchot represented all the ranks in Tzivos Hashem, and could therefore not be limited to just one.

The history of Tzivos Hashem is truly astonishing. Having begun with a handful of children in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, the organization rapidly grew to over 100,000 young Jewish children ranging in age from birth to Bar and Bat Mitzvah, with branches in countries around the world.

In Russia Tzivos Hashem has been very active organizing the same system of ranks and youth groups as were initiated here. Activities have also centered around setting up homes for orphaned and abused children, one for boys and one for girls, in Dnepropetrovsk, the city where the Rebbe’s father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, was the Rav, and where the Rebbe’s childhood was spent.

The synagogue where the Rebbe’s father worshipped, rudely converted into a warehouse during the Communist Era, was miraculously acquired by Tzivos Hashem a few years ago, and refurbished as an orphan home for boys, bearing the name of my sister-in-law and her late husband, Dr. William and Esther Benenson, who sponsored the project.

When I consider the strides and accomplishments of this organization, my heart swells with pride, and I feel honored that I was called upon to become involved when the Rebbe first initiated his new idea of Tzivos Hashem.

The Torah Picture

It was a few years after Tzivos Hashem got started, on an evening in 1983, that Yossi Raichik unexpectedly appeared again at the entrance of my home, with a new emergency project which the Rebbe had announced earlier in the day.

Fully cognizant of the deep divisions among the Jewish people brought about by the war, the Rebbe had decided to launch a massive Torah writing campaign to help ease the tensions amongst our people, and unite Jews from all walks of life in the Mitzvah of writing a Torah scroll.

The Rebbe was anxious to have a picture made that would symbolically convey the universality of a Torah writing campaign of this magnitude. Again, it was the Rebbe’s deep feeling that art would be a major factor in conveying the message.

I immediately envisioned the picture.

The painting was sketched to convey the idea that this project was not exclusively for Chassidim or Orthodox Jews. The Rebbe wanted all Jews to participate, men women and children.

The cost of writing of a Sefer Torah is at present approximately $30 - $35,000. Yet the maximum contribution allowed by the Rebbe was $1.00 for the purchase of a single letter. We are taught that every letter in the Torah is equally important, and that if a single letter is scratched, chipped or in any was blemished, the entire Torah cannot be used until it is repaired. Similarly, it is taught that every Jew has a letter in the Torah, his or her own ‘soul-letter,’ if you will. The Rebbe’s idea was to emphasize the equality and the importance of each and every Jew, and to establish bonds of unity amongst them, regardless of their background or affiliation.

Lag B’omer Book — The 33d Day Of Omer

The Rebbe always promoted festive events, parades and rallies for children. Lag B’omer is an outstanding example. Lag B’Omer is the 33rd day after the beginning of Passover, ‘Lag’ being the equivalent in Hebrew letters for the number 33.

Traditionally, children congregate in parks to sing and dance and spend the day celebrating the end of the mourning period for the thousands of Torah students who mysteriously died during the time of Rabbi Akiva, during the first 32 days of the Omer. It also marks the yahrzeit of the great Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, author of the Zohar, who asked that this day be honored for all time as a great festival.

Parties and events are organized world-wide on this day. In Chabad circles, Lag B’Omer is a day when great miracles are to be seen, especially with regards to children. And when Lag B’Omer falls on a Sunday, the Rebbe always orders a gala fair and parade for thousands of children, to take place in Crown Heights. It’s carnival time in Brooklyn, with food, merchandise, booths and kiddy rides galore.

The Rebbe personally reviews the parade, and delivers an important address to the children. On one such occasion, the Rebbe spoke in Russian for at least half an hour to these American boys and girls. They were totally bewildered, but the words found their mark behind the Iron Curtain, where they were soon played and replayed amongst refuskniks and underground Chassidim struggling at that time to keep Judaism alive.

With his flare for publicity, the Rebbe wanted to elevate Jewish awareness of the importance of Lag B’Omer. First he asked that his emissaries throughout the world send in pictures of parades, with letters from the children who participated, to chronicle the events. As the responses poured in from every corner of the globe, in so many different languages, I heard the familiar knock at my door.

I was told that the Rebbe wanted the pictures and letters to be made into an album. Text had to be composed. Captions for the pictures had to be written. Most urgently, the material had to be collected and arranged in a meaningful and effective format.

And so the Lag B’Omer Parade Album was born. Since it was a new project, the Rebbe personally supervised the production. I worked directly with Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, the Rebbe’s secretary, and director of Public Relations.

I remember vividly that whenever I met the Rebbe, he would always prod, “See that the book is finished for Pesach.” Of course I assured him that I would do all in my power to accomplish this.

It was frustrating that a number of places were very late in sending in pictures of their parades or letters from the children. However, when the final submissions arrived from some ten or twelve countries, particularly from north Africa and the Middle East, it turned out that they were well worth waiting for.

When I met the Rebbe again on the eve of Passover, 1982, and he asked, “What’s with the book?” I was able to assure him at last that the book would be ready for the forthcoming Lag B’Omer.

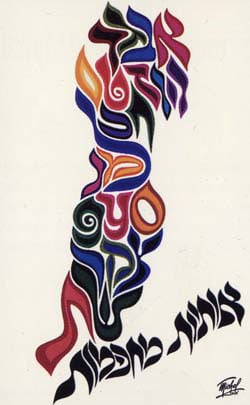

Before we went to press, the Rebbe asked to see the finished printed proof of the cover, for which I had created a painting, in the which the letters of “Lag B’omer” took the form of a traditional Lag B’Omer bonfire.

Accompanied by my dear friend, Rabbi J. J. Hecht, I met with the Rebbe as soon as the proofs came off the press. The Rebbe looked at the painting carefully, then thanked me for a job (finally) well done. By now, he no longer asked for preliminary sketches. He was obviously satisfied that the work would turn out well.

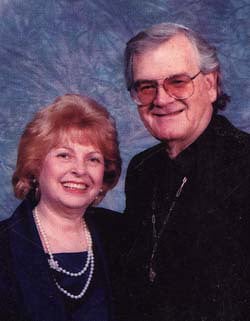

After our meeting, the Rebbe gave me his blessing, and prepared to leave his office. As he approached the exit, he suddenly turned to me and said, “Give my blessing to Mrs. Schwartz also.”

I always suspected that someone must have let him know about the many hours of the night and day that I had spent completing the book. With his typical thoughtfulness, the Rebbe made sure that my wife, Josepha, received the blessingshe so rightly deserved.

The Cup of Elijah

While my wife and I were living in Jerusalem, for a period of five years (from 1984-1989), several local well-known silversmiths approached me insisting that I create Judaica. They spoke about the vast array of religious ceremonial objects needed for various religious events, and argued that new designs would be most welcome.

I resisted, however, because I did not wish to produce designs for work which I would not be able to fashion by myself out of the desired materials.

One day, during a Judaic Art Fair held at the Jerusalem Hilton, where I was exhibiting my artwork along with approximately 70 other craftsmen, I stopped at a booth which caught my eye. It was the “Netafim” display of the Brothers Netaf, Jerusalem.

Eli Netaf asked why I did not enter the Judaica field. My designs were unique. My use of letters was well known, and any designs I would create, he promised to produce faithfully, no matter how complicated. It was a very strong argument.

I said I would think about it, stipulating, however, that if I should I decide to submit a design, it would remain proprietarily exclusively mine. We agreed that they would have the right to produce the designs for me by contract, but I would retain independent rights to market the product.

That afternoon, my wife and I took some time off from the exhibition to visit a cousin and dear friend who was confined to hospital in Petah Tikva. While we sat patiently in the visitors lounge, I busied myself with my ever-present pad and pen, and sketched a design for a “Cup of Elijah,” the “Cup of Cups” of Jewish ceremonials.

The Cup of Elijah is the special ornamental cup used during the Passover Seder, filled to the brim with traditional sweet Passover wine. Usually it is made of fine silver, or even gold. No one drinks from this cup except the Prophet Elijah, eagerly awaited during the Passover Seder, when he comes to visit every home, hopefully bringing word of the long-awaited coming of Moshiach, and the liberation of the Jews from all hatred and persecution.

Designing this cup was a great challenge. I wanted to create something very special, in my own style and shape, consisting of myriads of letters, that would tell the story of Elijah. I sketched a cup which had as its design, a “screen” of letters surrounding a cylindrical cup, perched on an elegant pedestal.

The verse I chose was the song in praise of Elijah, written centuries ago by an unknown poet, expressing the yearning for the Moshiach. It is chanted in homes all over the world, on Saturday evening, when the Holy Day of Shabbat comes to an end, and the new week begins.

In our home, which was traditional in every way, I remember this beautiful ceremony which my father would perform with the entire family in attendance, my mother, four sisters and two brothers.

The Havdallah service was recited by my father in the traditional chant. My younger sister would hold the woven beeswax Havdallah candle as high aloft as she could, “so she would marry a tall groom.” The blessing over the spice box was made, and Sabbath Day was then over.

After this very beautiful ceremony, we all joined in singing songs, for we were a family blessed with musical talent. Our favorite song, which was by far the most harmonious, was “Elijah the Prophet, Elijah the Tishbi, Elijah the Giladi, may he come soon with Moshiach, the son of David.”

This was the hymn for the words with which to decorate the “Cup of Elijah.”

Fashioned of pure silver with gold overlays, the cup was immaculately recreated by the silverworks of the Netaf Brothers. And so a classic new style of Judaica was born. I was impressed beyond my own expectations.

Approximately two months later, my brother Moshe, who for many years was involved in helping me research the verses and correctness of my Judaic designs and paintings, was in America for a visit. On a bright sunny Sunday morning he decided to visit the Lubavitcher Rebbe, whom he had known for many years, having been recruited by the previous Rebbe, the Rebbe’s father-in-law, Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn, as part of one of the earliest groups of emissaries for Chabad outreach in cities around the country. I suggested that he take the Cup of Elijah with him to show the Rebbe.

When he arrived, after receiving the Rebbe’s blessings, and 28 crisp new dollar bills for his 28 grandchildren, he showed the Rebbe “The Cup of Elijah.” The Rebbe studied the cup deeply as Moshe described its content and design. Then the Rebbe said, “Nu, is Michel already in production?”

To which Moshe responded, “No, not yet. However, this is the prototype and the only one in existence at present.”

The Rebbe studied the cup again, and asked, “Nu, if this is the only one, will it be left for me?”

Now, we must make something perfectly clear. The Rebbe here broke all protocol. As far as anyone could recall, including those who had served the Rebbe since the first day, for more than 35 years, the Rebbe had never in the past asked for a gift. Gifts were often presented to him, as one can imagine, but this was the first time that the Rebbe actually requested one! And public, on a Sunday Dollar Day, he requested the “Cup of Elijah” for himself.

Moshe was taken aback by this request, and somewhat embarrassed. At a loss for words, he apologized that he could not leave the Cup with the Rebbe, “because I was not instructed to do so by Michel. However, he would surely appreciate the Rebbe’s blessing.”

With a wonderful smile, the Rebbe gave his blessing, and bade Moshe a safe journey back to Israel.

Excitedly, Moshe drove straight back to our home. “Michel, you won’t believe what happened!!” he announced, and began to tell me all the details. He was right. I could hardly believe that the Rebbe had asked for this “present” so plainly.

It was well-known that videotapes were made whenever the Rebbe met publicly with guests and visitors, on Sunday or on other occasions. The tapes are dated, and available for review by anyone who requests a copy. Immediately we called to see if a tape of Moshe’s interview with the Rebbe was available. Sure enough, they promised that we could have a copy by 3 pm that same afternoon. Back Moshe drove to Crown Heights, to the processor of all photography and video taping, and purchased three copies of his encounter earlier in the day, Then quickly he returned to me.

Immediately I played the tape, and with great personal satisfaction, witnessed this singular historic occasion, when the Rebbe personally and publicly asked that the cup I had designed become his personal property.

After watching the tape at least 10 times, there was no question in my mind that the Rebbe should have his wish, and I decided on a plan to accomplish it. I contacted an old and loyal benefactor of my work, Belle and Jacob Rosenbaum of Monsey, New York, and told them what had happened earlier. They replied with astonished disbelief – “It can’t be! It never happened before!” I offered to drive up to their home and show them the video.

Both Belle and Jack were anxiously waiting to see the tape. After a few moments of discussion, I put on the tape. Their reaction was just as I had expected. They were eager to pay for the “Cup,” and wanted to present it personally to the Rebbe, as soon as feasible.

They also ordered a second “Cup” for their own collection, for which they would pay my actual cost price. I accepted their offer, with the proviso that my wife, Josepha, and myself would accompany them in presenting the “Cup” to the Rebbe as a gift.

No matter how long one knows the Rebbe, no matter how many times one has been to see him, the thrill of another visit with this great human being is always unique. In this case, the timing was significant, as Passover was approaching, and the Rebbe’s birthday, Yud-Aleph Nissan, the 11th day of the month of Nissan, was a mere 2 weeks off. The Rebbe had no inkling that we were coming to fulfill his request to “leave the Cup of Elijah for him.”

As the Rosenbaums, Josepha and I approached the Rebbe, I took the initiative and announced that I was happy to be able to fulfill his request, and present him with the Cup of Elijah as a gift, made possible by Belle and Jack Rosenbaum. I introduced the Rosenbaums, and my wife and myself as partners in the presentation, and handed the Cup to the Rebbe.

We will never forget this moment as the Rebbe received the gift with a smile and placed it on the table near him.

He then went on to offer his blessings to each of us individually. Tears welled in the eyes of Belle and Jack, as she spoke to the Rebbe about their long support of Lubavitcher programs. Jack had been the President of Bris Avrahom, an organization which performed the circumcision rites for thousands of Russian immigrantswho had never had a Bris in the Soviet Union under Communist rule. Bris Avrohom, under the leadership of Rabbi Mordechai Kanelsky and his Rebbetzin Shterna, was originally created at the behest of the Rebbe, when the tens of thousands of new Russian immigrants began to arrive in America.

Having received the Rebbe’s blessings for ourselves individually, as well as on behalf of all our children and grandchildren, we departed in a spirit of overwhelming satisfaction, at having had the privilege of making this presentation to the Rebbe for his 86th birthday.

For several years after the Rebbe received the Cup, I wondered what happened to it. I hoped that perhaps it might have been used at the Seder table, but I never heard a thing about it from anyone who might have known.

One day, it happened that I had to enter the hospital for an angioplasty procedure. I decided to stop in at 770 to ask Rabbi Groner to mention this to the Rebbe and ask him for a blessing on my behalf.

When I arrived at 770, Rabbi Groner was with Rebbe. This was some time after the Rebbe had suffered his stroke in Adar 1992. As I waited for Rabbi Groner to emerge from the Rebbe’s room, I was engaged in conversation with one of the team of Chassidim, who stood twenty-four hour watch, as part of the Hatzalah Ambulance Corps, to be available at a moment’s notice in case of emergency.

The attendant at this time was an old friend, Leible Bistritsky. During the conversation, he said, “You know, Michel, the Cup you gave the Rebbe, since the Rebbe became ill, it has been standing on a small round table at his bedside day and night. It is never removed for any reason, and you know, we are in his room 24 hours a day.”

I was absolutely stunned. I now heard for the first time, the whereabouts of my goblet, the “Cup of Elijah.”

I didn’t know what to say. Just then, Rabbi Groner emerged from the Rebbe’s room. I followed him into his office, a small side room where he spends days and nights meeting literally thousands of people, Chassidim, well-wishers, and dignitaries, seeking the Rebbe’s blessing.

I told Rabbi Groner about my impending heart procedure and gave him a paper with my Hebrew name and my mother’s name, which had to be included in the blessing.

Then I said, “By the way, Bistritsky just mentioned to me that since the Rebbe took ill, the goblet has been standing next to him, day and night, and is never moved out his sight. Could that be?”

Rabbi Groner looked at me, stroked his flowing, graying beard, and replied, “No, Michel. Not since he became sick. Your cup had been in his room since the day you presented it to him, for over 4 years.”

I was momentarily at a loss for words. Than Rabbi Groner continued, “Also the small round table which the goblet sits on is a wooden table which the Rebbe Maharash personally made.” The Rebbe Shmuel, known as the Maharash, was the fourth Rebbe of Lubavitch. It seems that he suffered greatly from illness during his lifetime. It was suggested at one point that he take up carpentry as a form of therapy, and one of the works he completed was this table. It was given down to the Rebbe after the War, in Paris, by a descendent of the Rebbe Maharash.

Rabbi Groner also mentioned that there were two walking sticks which leaned on this table at all times. One had belonged to the famous Rabbi Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev, and the other had belonged to the Rebbe Rashab, Rabbi Sholom Dovber, the 5th Lubavitcher Rebbe.

I listened intently, not uttering a word. I was awestruck, that my Cup of Elijah had joined such exalted company. I thanked Groner for accepting my note for a brocho, and soon afterwards I left.

“When Moshiach Comes”

“....And now, Michel, I want you to make another picture.... of what the world will look like when Moshiach will come!”

This historic “commission” was put to me in these simple words, spoken in Yiddish, at ”Sunday dollars,” on September 24th, 1989.

I stood there speechless, completely taken by surprise; but without hesitation, I accepted this most unexpected and historically unprecedented request.

During my 45 years of working with the Rebbe, I could not recall that he ever requested anything like this from anyone. There was absolutely no elaboration on his part. It was truly out of the ordinary.

I doubt if there has ever been a similar request to any artist in Jewish history, put forth by any other Rebbe or religious leader of stature.

The Jewish tradition does not generally allow for Rebbes to request paintings to be created for any reason. Nowhere in the Torah, in the descriptions of the Tabernacle, or the Holy Temple, is there any reference of artists decorating these public edifices with paintings, mosaics or carvings.

Betzalel and Oholiav received detailed descriptions from God to create all of the Holy utensils, curtains and furniture of the Holy Sanctuary, the Tabernacle; but there is no mention of art for decorative purposes or education. Neither is there mention of such specific graphic commissions in any later writings of the Sages.

Yet, here was a saintly scholar, revered by millions of Jews around the world for his sagacious insight and brilliance, asking me to create a scenario of what the world will look like upon the arrival of Moshiach.

Even more bewildering, I wondered, why was the Rebbe asking me? The Jewish world has developed a great number of recognized artists with enormous abilities in detailed illustration, anatomy, imagination, and all those talents that would be necessary to create this scene. Why me?

I accepted the challenge at once, and thanked the Rebbe, as he gave me five $1 dollar bills together with his blessing. All the way home, in my car, I kept thinking of the awesome task ahead of me. I truly did not know what to do.

First, I decided, I must consult with the two people who were extremely close to the Rebbe and who might perhaps have a suggestion as to what the Rebbe may have meant. Perhaps a clue as to the contents or appearance of this painting. Something. It was a long shot, but I had to speak with them.

I returned to 770 later that afternoon, when I expected that “dollars” would have ended, and Rabbi Groner would be back in his office. I arrived at approximately 5 pm. As I thought, there was a cue of people waiting to present Rabbi Groner with slips of paper containing their various requests from the Rebbe, for his blessing, or seeking answers to questions or problems they may have had.

I used an outside phone and called his direct line. He recommended that I go quickly to his office door, knock, and come in, so that he could see me. I did so, and he immediately asked me to enter his office.

“I came to see you,” I said “because of my conversation with the Rebbe, which you witnessed. I am hoping that perhaps you may guide me in this matter. Maybe you can tell me something.”

“Michel,” was his reply, “I am just as surprised as you. However, if the Rebbe asked you to do such a painting, then he thinks you have the genius to do it.” Then in a somber voice he said, “So do it!”

I realized then that Rabbi Groner would not intervene with the Rebbe, nor would he answer me in a more specific way. I saw no purpose in pressing the issue with him. I thanked him and told him I would be in touch as soon as I came up with an answer to this task.

I then walked over to see my good friend and fan, Rabbi Jacob J. Hecht. Fortunately he was still at his desk in his office at the National Committee for the Furtherance of Jewish Education, located less than a block away on Eastern Parkway. I entered his room, and immediately he greeted me with, “So the Rebbe served you curveball, and you’ve gotta hit a homerun! There’s just no other way.” I asked him what he thought the Rebbe meant.

“Look”, he said, “the Rebbe knows what he wants, so I suggest you write him a letter, asking him what he envisages, and I’ll see that he gets the letter. He will surely answer you very quickly.”

I realized right then and there, that not a single Chassid would come forward, or have the audacious courage to interpret such a request by the Rebbe. “Yankel,” I said, “I appreciate the gesture, but thanks. I guess I will have to solve this one myself.”

As Rabbi Groner had said, if the Rebbe was confident in me, I figured that I would be able to solve the problem myself.

I immediately visualized a picture than the portrait had been, on a much larger scale. One which would contain as many references as can be found in the Torah, Prophets, the Writings, the Mishna, Talmud and Sages, all the prophecies about the coming of Moshiach.

I would confine the painting to 304,805 letters, which is the exact number of letters in the Torah. It would be very large in proportion. I envisioned the canvas approximately 6 feet by 4½ feet. The letters would be half an inch in height. Superimposed on this canvas of letters would be many illustrations pertaining to the prophecies of the great scholars, authors and teachers of our people through the centuries.

I visualized a monumental piece of art that would take years of research. I just knew, I had that positive feeling, that my search was over.

It was Friday afternoon, the one day during the week that Rabbi Groner leaves the Rebbe and gets ready for Shabbat. It is also the one time that I can get him at home. So I did.

Rabbi Groner answered the call, and I excitedly described to him what I thought the painting would be. I told him that I hoped to get started as soon as possible. Then I asked him for an appointment to see the Rebbe on Sunday. “Be there at 1:30,” he said.

On Sunday, at 1:30, I was ushered past the crowds directly to the Rebbe. When I approached, the Rebbe recognized me with his winning smile, and we shook hands. I bent over his right shoulder and said, in Yiddish, “Rebbe, I now have an idea for the picture that you asked me to do.”

Before I could continue he looked at me and said, “But it should be made of many, many letters, so you can earn from it a lot of money, so you can give a lot of Tzedakah!”

Rabbi Groner, in amazement, with both hands outstretched was saying, “Michel, that’s just what you said! That’s just what you said!”

I then answered the Rebbe, “the picture will contain 304,805 letters.”

He immediately replied, “That is exactly how many letters there are in the Torah!”

I then continued, “The letters will describe through excerpts from the Tanach, Mishna, Talmud and other sources, what the world will be like when Moshiach comes. I will illustrate these prophecies over the background.”

Once again I received the Rebbe’s blessing, and dollar bills for Tzedakah. I departed a very, very happy man. I realized that I truly had arrived at the exact same idea that the Rebbe had apparently had in mind.

The incident was not lost on those who were present, nor on many others who heard about it.

Then the work began. Initially the task was to gather the thousands of references to Moshiach, which I needed for the background of the painting. For this task, I was blessed with a brother, a Torah scholar, who had himself studied in the Lubavitch Yeshiva, as well as Torah VaDaath, and Yeshiva University. Without his devotion and assistance I would have been at a great loss.

I would never have been able to find, call out and document the massive amount of material that needed to be reviewed and transcribed. Not only did he wade nights into the task, he researched a great number of resources both in the United States and Israel, much of it by the use of computer centers. It should be noted to his credit, that in 1992, the computer archives were not as complete as they are today, so the task was a difficult one.

As he fed me Xerox copies of the text, beginning with Isaiah, I was transcribing them directly onto my canvas. It took us almost a whole day to rule out a sheet of fine hand-made heavy archival paper, spacing the lines 7 to the inch, the width of the sheet was 75” and the depth 48”. Mathematically we determined the number of lines we would need to write out 304,805 letters, multiplying the number of letters per line by the number of lines on the canvas.

I decided to use a mechanical pen with an extremely fine stainless steel point. The ink I used was of the finest quality imported from Windsor-Newton of England. The key to my writing the letters was that I had to draw an open-face or outline letter. If I simply used a standard calligraphy pen, the entire page would be a black blotch. By doing the script in outline I effected an overall grey color, and I planned to selectively emphasize certain words by doubling the size of the letters.

Unlike certain artists of days gone by, who were subsidized by a gallery or patrons of wealth, I had to finance myself. I usually began to transcribe my manuscript at the end of the day, around 4 or 5 PM, and worked straight through.

All in all, it took more than 2500 hours of work. When I informed the Rebbe that the conclusion of the painting was nearing, he asked specifically that it be done by his 90th birthday.

In the end, the painting was not 304,805 letters, as I had envisioned, but 387,000 letters.

For over a year, the picture was on display at the Fifth Avenue Synagogue. Privately, I always wanted it to be exhibited in a museum or some place where multitudes of people could view it and understand the meaning of the Rebbe’s desire for the arrival of Moshiach.

As a footnote, I would add that the Moshiach picture has spurred an even more ambitious undertaking to begin this year. I will be painting another picture which will surpass all of my other micrographics put together. I will paint a picture whose background will consist of approximately a million letters. I intend to paint a statement on Jerusalem by writing every reference, every sentence of statement where Jerusalem is discussed in our Ta’nach, the Mishnayot, Talmud, later Rabbinical writings, references by authors, sages, poets, philosophers, historians and archaeologists.

The research for this project is well under way. When the text for the painting is done, I intend, with Hashem’s help, to overpaint the history of the Jewish people.

Join the Discussion