My wife, Rochel, and I arrived in South Africa in March, 1976, three short months before the Soweto uprising which would become a major milestone in the eventual fall of the racist Apartheid regime. The country was in turmoil. Masses of white families were leaving in droves. People here told us they couldn’t understand how a young couple with two small children would move to South Africa when everyone else was leaving. “Are you mad? Don’t you know we’re sitting on a volcano?!”

But we were here on a mission. We were shluchim, emissaries of our mentor and teacher, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, who sent us here to do the work of spreading Judaism in Johannesburg. My friend, Rabbi Mendel Lipskar, had been sent here by the Rebbe four years earlier. When an old boarding house in Yeoville, the major Jewish neighborhood at the time, was purchased to serve as this country’s very first Chabad House, I was invited to come and take the position of Founding Director.

I had a number of other attractive job offers overseas too, and put them before the Rebbe. The Rebbe chose Johannesburg and, thank G‑d, we have never looked back.

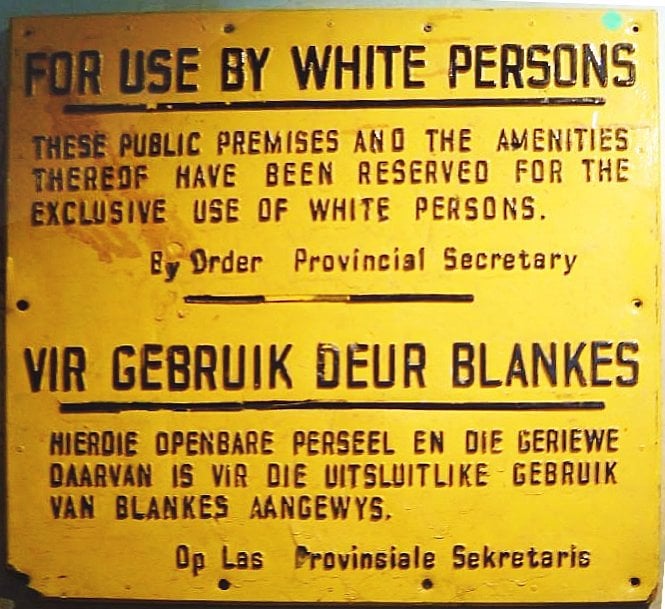

But at the time Apartheid was in full force. The park benches had signs stating, “Whites Only.” There were separate buses, separate waiting lines in the post office, separate counters in the liquor stores. And there was palpable anxiety in the heart of virtually every white South African.

Many of those moving to other shores said it was on moral grounds. Their principles wouldn’t allow them to live in an apartheid state. Personally, I suspect that most were leaving out of fear. What did the future hold for South Africa? The proverbial winds of change were gusting across the continent. Would we go the way of other African states? Would we, too, face a bloody revolution with a million Zulus marching through the streets with spears?!

In those days there was virtually no Jewish family that was not grappling with the vexing dilemma of emigration. To go, or not to go, that was the question.

In the 70s and 80s there were not many South African-born rabbis here. With the political situation so volatile, British and American rabbis were no longer considering positions here, and even rabbis who were already here were leaving. So many families were emigrating that our community was being decimated. What would become of all our schools, shuls, and our proud institutional infrastructure?

During this period of uncertainty, the Rebbe sent his rabbinical students to serve this community as his emissaries, giving South Africa a massive vote of confidence.

But his direct responses to the questions so many South African Jews were putting to him were even more encouraging. The Rebbe was completely dismissive of the perceived need to emigrate. There were no grey areas and no vague platitudes. He said clearly that we should not be afraid and we should carry on with our good work. Some people were even advised to return here after they had already left!

His continuous reassurances of confidence spread like wildfire throughout the country. “The Rebbe” became a household name in South Africa. Even people not involved in religious life boasted that they would “close the lights at Jan Smuts Airport” based on his promises. (Today, the Johannesburg International Airport is known as OR Tambo, after the great freedom fighter Oliver Tambo.)

In 1977, on the Rebbe’s birthday, just a few days before Pesach, he addressed thousands gathered for a public farbrengen to mark the occasion. I was there visiting, and was asked by Rabbi N.M. Bernhard to introduce Mr. Abe Hoppenstein (then a consular official working at the South African Embassy in Washington) to the Rebbe. Abe flew in specially from Washington, and I made the introduction during the singing between the Rebbe’s talks. I vividly recall how the Rebbe mandated him to relay the message to South Africa’s Jewish leaders that the community should not pack up and leave, but on the contrary, should continue to build and develop Jewish schools, synagogues, yeshivas, mikvahs, etc.

Others may have been planning museums to remember the soon-to-be-defunct Jewish community of South Africa, but the Rebbe was inspiring us all to stay and be strong and build for a brighter future, confident that white and black South Africans could peacefully coexist.

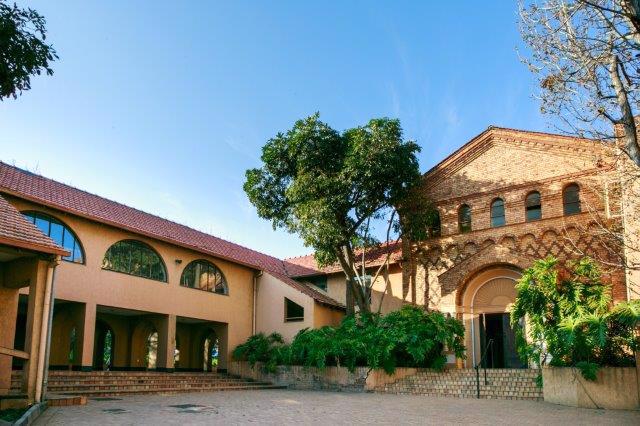

In 1979, with its small school in Yeoville now bursting at the seams, the Lubavitch Foundation purchased a large tract of land in the prime northern suburbs of Johannesburg. Property prices were down, and it was an unbelievably good deal. The Torah Academy would now be able to expand and unlock much exciting potential.

But the lay leaders of this community, namely the Jewish Board of Deputies, Zionist Federation, Board of Jewish Education, Israel United Appeal and United Communal Fund all attempted to prevail upon us that we should abandon our “reckless empire building.” South African Jewry was “in decline,” they stressed. There wouldn’t be enough children or sufficient financial resources in the community to support another stream of Jewish education, they argued. When we respectfully disagreed, they wrote a letter to the Rebbe, signed by the Chairmen of the Board and the Federation, asking him to curb his errant emissaries.

The Rebbe responded with a long letter encouraging those lay leaders to do their utmost to reverse the very decline they had referred to. He praised our strong, warmly traditional Jewish community and also highlighted its proud relationship with Israel. He further pointed out that Jewish communities the world over played an important partner role with Israel in influencing their local governments to maintain positive international relations with the Jewish state. We had to do our part, too.

On three separate occasions, Chabad leaders here were under pressure from a very nervous community clamoring to know if the Rebbe still maintained his confidence in our future. One of these was in August 1985 when President P.W. Botha delivered his infamous Rubicon speech in Durban. I will never forget how on each occasion, the Rebbe reiterated his position stating the same two word Hebrew answer: “l’peleh hashaalah! – It is astounding that you even asked the question!” In fact, his was virtually the only voice of hope and optimism in those difficult years.

There were sanctions, global pressure, civil violence, and eventually, on February 11, 1990, South African President F.W. De Klerk announced the release of the world’s most famous political prisoner, Nelson Mandela. But as historic and heady a moment as it was, it created new apprehensions and uncertainties. What would the future now hold for South African Jews?

On the very day of Mandela’s release from prison, Rabbi Koppel Bacher, a prominent local Chabad leader, was in New York. On Sunday, he stood in line to receive a dollar for charity and a blessing from the Rebbe. After giving him the dollar for tzedakah, the Rebbe called him back and gave him this message for our community. “Tell them they have nothing to fear and that South Africa will be good for Jews until the coming of Moshiach!”

Then we enjoyed the dawn of a new dispensation, and Nelson Mandela was elected president in the country’s first free and fair national election. New hope arose. One of the original members of those communal organizations who discouraged us from developing our school called me and said that in his view, “The Rebbe was now vindicated!” I could only smile.

But then, the burgeoning crime rate became a new cause of emigration. Not only were many of my congregants becoming victims of crime, I too was hijacked—ironically, while going to visit the shiva house for a man who had been murdered.

Rochel’s hijacking story was far more dramatic. The would-be hijacker actually pulled the trigger twice at point-blank range. Miraculously, nothing happened–twice! By a miracle of G‑d, my dear wife was spared.

Many wondered how any human could confidently tell people not to leave such a danger zone. Was this not irresponsible, even reckless?! My own answer was simple. I said that for any man sitting on the other side of the world to answer questions of such magnitude, he had to be either a prophet or a fool. Well, one thing was for sure. This giant of a man, this extraordinary Torah sage and saintly luminary was certainly no fool.

In the end, the Rebbe’s unequivocal assurances were indeed vindicated. And yes, looking back, they were in fact quite prophetic. And that contentious Chabad school, The Torah Academy? Today it boasts over 600 students.

Eventually, emigration would lead to a huge loss in numbers for South African Jewry, some half of our population.

Apparently, the Rebbe commented that while he had not been as successful as he would have liked in stemming emigration from South Africa altogether, he was gratified that he had succeeded sufficiently for the community to survive with stability and vibrancy.

As I look back at 26 years of democracy in South Africa, the third of Tammuz this year (25 June, 2020) will also mark the 26th yahrtzeit of this colossal Jewish leader of our time. Looking at our community today and imagining how different it might have been, G‑d forbid, do we not owe him a huge hakarat hatov, an eternal debt of gratitude?

I, for one, think it is long overdue.

Join the Discussion