Among the various ethnicities and cultures that make up Klal Yisrael, the entirety of the Jewish nation, a special place is occupied by Yekkes, Jews from Germany.

Punctilious and particular, the stereotypical Yekke is a creature of habit, reliable, devout, and exact. He or she is also skeptical and ambivalent toward vagaries or anything that cannot be quantified, qualified, and documented.

1. The Term Is Both Laudatory and Mildly Derogatory

The Internet abounds with theories regarding the term Yekke and how it came to refer to Jewish people of German extraction, some positing that it comes from the German word for “jacket,” since German Jews tended to wear short suit jackets, not the long frocks of their Eastern European contemporaries. Whatever its source, the term is both a badge of pride and an expression of derision, which is used in a variety of ways: “That Yekke is amazing, never a single minute late!” but also, “That Yekke gets all bent out of shape when I’m even a single minute late!”

2. They Are the First Ashkenazim

Ashkenaz is the Hebrew name assigned to Germany. The various migrations of Europe’s persecuted Jews over the centuries have meant that, on one hand, Ashkenazi culture spread far east into the Russian Empire. Yet, within the big-tent Ashkenazi universe, Ashkenaz still referred specifically to German Jews, and even more specifically to those from Southern and Western Germany.

3. They Have Unique Customs

The Jews of Germany have their own unique customs, some of which are shared amongst all Yekkes, and some of which are particular to a specific region or city.

Some of the most noticeable synagogue customs are that boys begin wearing a tallit (prayer shawl) from a young age, and the wimpel—a Torah sash made to honor each child born into the congregation.

Another difference is that on Shabbat and holidays, they wash for bread before reciting Kiddush and then break bread immediately after partaking from the Kiddush wine.

4. Synagogue Tunes Are Very Exact

Synagogues following German rites have specific tunes unique to each holiday and even special Shabbats throughout the year. For example, on the Shabbat of Chanukah, Adon Olam is sung to the tune of Maoz Tzur, and on Passover, to the melody of Adir Hu (which is sung after the Seder).

Thus a Yekke can enter a synagogue any day of the year and, without even hearing what is said, can identify the (approximate) calendar date as well as where the congregation is up to in the service.

5. They Had Their Own Form of Yiddish

While Yiddish shares a common ancestor with modern German, it is, of course, a different language with many unique features. Traditionally German Jews spoke a unique dialect of “Yiddish Deutsch” (German Yiddish), which (quite understandably) was more similar to German than was its eastern counterpart, which evolved in a Slavic milieu and was thus less influenced by the German language.

As German Jews assimilated (to varying degrees) into the wider German culture in the 19th century, the language effectively became extinct.

6. Assimilation Hit Early and Hard

As the Enlightenment swept through Western Europe, the walls of the ghettos came crashing down. Sadly, some German Jews were enticed by promises of acceptance and acculturation and converted to Christianity. Others chose to “reform” Judaism into a bland set of limited and sanitized rituals, which they hoped would allow them to become palatable to their German neighbors without needing to officially renounce their Judaism.

7. Frankfort Was a Bastion of Orthodoxy

Throughout Germany, there remained pockets of Jewish people who stayed faithful to the Judaism of their ancestors.1

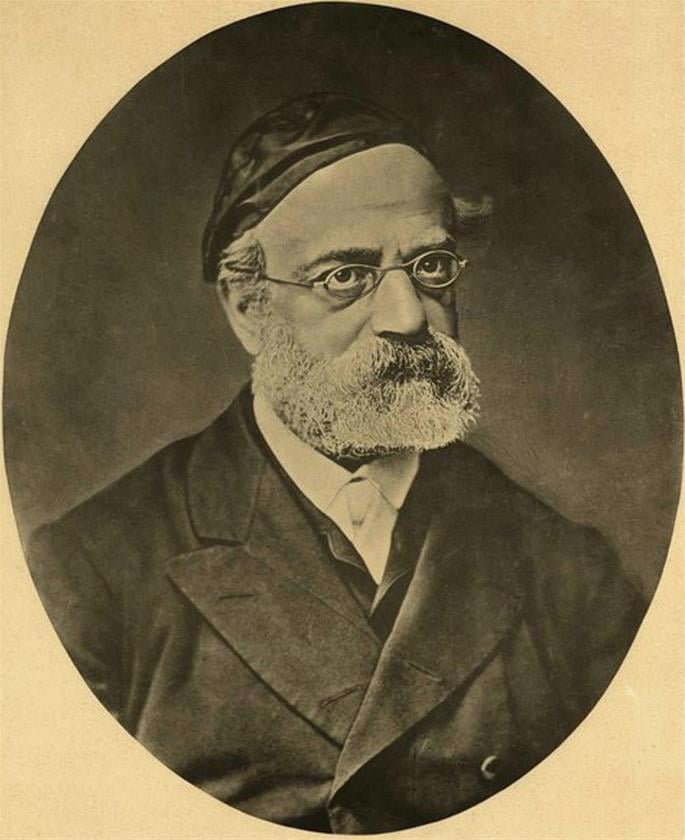

This was particularly pronounced in Frankfurt, where a separate Orthodox community was formed in an event known as the austritt. With members who were learned in Torah and also well educated in secular matters, the community became a model for others to follow.

8. They Adopted Western Appearances

While Eastern European Jewish males tended to maintain a distinct form of dress, including long coats, black hats, beards etc., the typical Yekke was not externally distinguishable from his neighbors. The rare exception was the rabbi, who typically wore prominent payot and sometimes also a beard.

9. Yekkes Have Their Own Hebrew Pronunciation

Four pronunciations of the cholam prevailed among pre-Holocaust Ashkenazic Jews: two in Eastern Europe and two in Western Europe.

Thus, the word cholam, for example, would be pronounced as choilam among Polish (and Austrian) Jews, chaylam among Lithuanian (and Russian) Jews, chaulam amongst northern Yekkes and cholam when pronounced by southern Yekkes.

It appears that German Jews also once differentiated between the aleph and ayin, and chet and chaf, but that seems to have fallen away by the 17th century.

10. They Referred to Prayer as Orenen

Influenced by Eastern European Yiddish, many American Jews use the word daven to refer to the act of prayer. Among Yekkes, the word oren was used, based on the Latin ora (“pray”).

11. They Often Had Two Names

Many German Jews had two names, their Hebrew name and a corresponding German (Yiddish) name. While a Jewish boy received his Hebrew name at his brit milah (circumcision), among western Yekkes the secular name was given at a separate ceremony known as hollekreisch.

12. There Were Three Tiers of Rabbinic Ordination

Among Yekkes (and also Austrian Jews), a person who had studied in yeshivah and was capable of independent study was given the title chaver (“peer”), which was technically not ordination. An advanced scholar was known as a rav (“rabbi”). One who actually issued Torah guidance on a communal level was referred to as moreinu (“our master”).

13. Yizkor Was Not Said on Holidays

Like Sephardim, Ashkenazim traditionally did not say Yizkor on Passover, Sukkot, and Shavuot (some congregations did say it on Yom Kippur) since the melancholy nature of remembering our departed loved ones would detract from the joyous holiday.

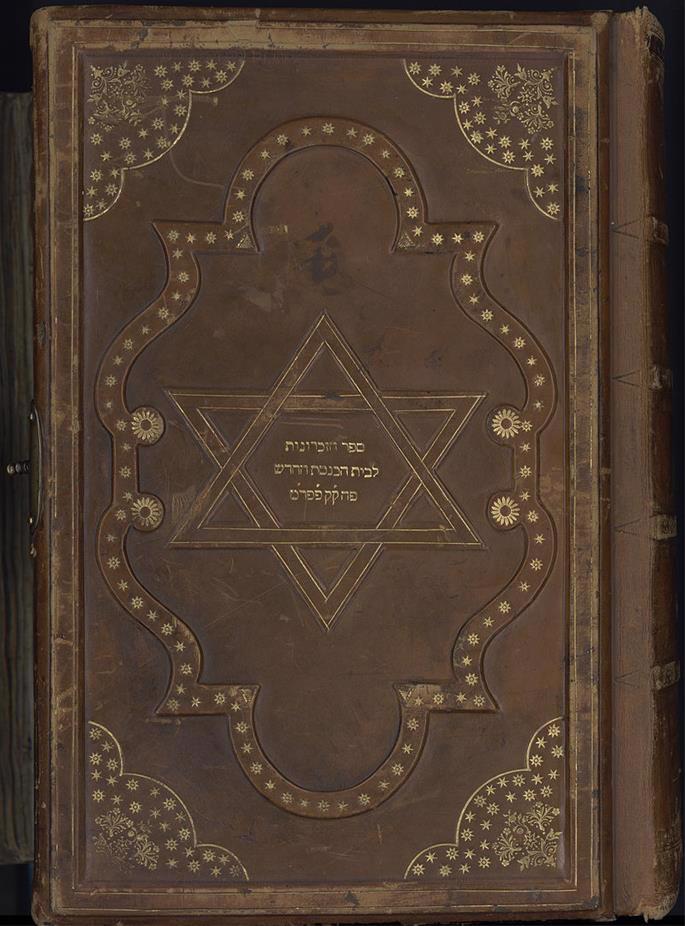

Instead, on two specific Shabbats during the year, they pulled out the memorbuch, which contained records of the community’s loved ones going back centuries, and recited memorial prayers for them all.

14. Yekke Life Was Transferred to the New World

With the rise of Naziism, it became increasingly clear that there was little future for German Jewry. Many escaped to the US, Mandatory Palestine, and other places, replanting their uprooted communities in their new surroundings.

In time, many Yekke communities faded and the children and grandchildren of the original immigrants became one with the wider Jewish community. However, vibrant and distinct German-Jewish communities still remain, notably K'hal Adath Jeshurun in Manhattan's Washington Heights neighborhood, founded by transplants from Frankfurt, led by Rabbi Dr. Joseph Breuer (1883-1980).

15.There Is (New) Jewish Life in Germany

Following the Holocaust and resettlement of the Jewish survivors, few Jews remained in Germany. In 1952, the Jewish population was reported to be just 10,000, a mix of native-born Yekkes and Jews from elsewhere in Europe who ended up in Germany at the war’s conclusion and had not moved on.

Starting in the 1990s, German Jewish life flourished once again, as Jews from the USSR (as well as others) poured into the newly unified and prosperous country.

Today, there are more than 100,000 Jews in Germany, served by 35 Chabad emissary couples across 19 cities.2

Join the Discussion