BUENOS AIRES, Argentina—It was late 1984, and Argentina’s brutal military junta had fallen barely a year earlier. Yet as Chanukah approached, Rabbi Tzvi Grunblatt was determined to erect his country’s first public menorah.

Over the course of its seven-year stretch of power, the junta had spearheaded a campaign of terror against its opponents known as the “Dirty War.” At its height, thousands of dissidents and others had disappeared, kidnapped off the streets during the day or arrested as part of midnight raids in their homes. Today, the precise fate of thousands of victims remains unknown.

While the junta fell following its lopsided loss during the Falklands War, it had successfully instilled a culture of fear in Argentina. And now that Grunblatt wanted to construct a large Chanukah display in the center of Buenos Aires, many in the Jewish community were anxious and concerned about possible repercussions.

“People were very afraid during that time,” remembers Grunblatt, an Argentine who returned with his American-born wife, Shterna, in 1978 to direct Chabad Lubavitch of Argentina. “They said there was no way it would not bring anti-Semitism. There was one influential Jewish-community board member who said if it stands for 24 hours, he would put on tefillin.”

Leaning back in his chair, Grunblatt closes his eyes and thinks for a moment, recalling how the scenario played out. He opens his eyes and smiles. “He didn’t keep his promise.”

“There was one man who supported me, the late Mr. David Goldberg,who was the president of DAIA”—an acronym for Delegación de Asociaciones Israelitas Argentinas, Argentine Jewry’s umbrella organization—“at the time. He told me not to listen to anyone, and that we should do it.”

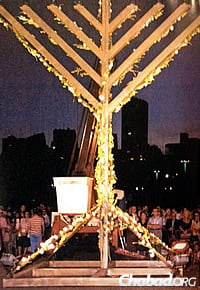

That year, the menorah went up. It was not knocked over; it stood there without incident, and, in fact, drew accolades from throughout the newly re-established democracy.

The lighting ceremony itself wound up drawing thousands of participants, with greetings read from President of the Republic Raúl Alfnosin. Press coverage beamed images of the historic event to hundreds of thousands of more people around the country, and an editorial in La Nación—one of the country’s largest daily newspapers—hailed the menorah-lighting as a sign that the era of fear Argentina had just experienced was finally coming to an end.

“People were shocked,” says Grunblatt. “The menorah was like a revolution here. They had never seen such an open display of Yiddishkeit before. The next year, in 1985, the community embraced it with open arms, and that’s how it’s been ever since.”

‘Chanukah on the Map’

While among American Jews Chanukah has long been one of the most observed holidays, Grunblatt explains that until recently, the holiday was hardly known by large segments of Argentina’s Jews largely due to its child-centric nature. And being that the country lies in the Southern Hemisphere, it falls over the summer, when families are out and about, and kids at camps or away from home.

“In Argentina, Chanukah usually begins right after the school year ends,” he says. “Because of that, most children didn’t really learn about it much in school or celebrate it there because they were on summer vacation. Chanukah wasn’t very widely known in Argentina, and no institution had any big programs for the holiday.”

Grunblatt credits the campaign started by the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—to spread awareness and the message of Chanukah with bringing holiday observance back to Argentina. “Today, all of the [Jewish] institutions have a menorah, and they all do Chanukah events. Because of Chabad, Chanukah here is on the map.”

Armando Reler, who served as executive director of Maccabi in Argentina for more than 20 years, agrees with Grunblatt’s assessment. “Chanukah for a lot of the Jewish community in Buenos Aires was playing football at Maccabi,” he explains. “Once in a while, someone might pull out a menorah and light it, but not much more than that. Later, when Chabad began lighting a menorah at the largest football stadium here, it was the Jews who were the most surprised!

“People were also afraid to show their Jewishness in public. Because of what Chabad has been doing, people realized that it’s possible to not only be Jewish, but to be Jewish publicly.”

In addition to the central menorah put up each year, others now dot the massive city all over, placed there by the more than two-dozen Chabad centers that have opened in the last three decades.

Honoring the 30th Anniversary

The event was scheduled for Wednesday, Dec. 17, but as the 8 p.m. starting time approached, rain started falling in buckets on Buenos Aires.

“We all thought it would have to be postponed to the next night because of the rain,” says Rabbi Mendy Gurevitch, director of the Wolfsohn-Tabacinic Jewish Day School and Community in the city’s Belgrano neighborhood. “It poured hard for 15 to 20 minutes, and then it suddenly stopped. People came from everywhere; it was a beautiful event.”

Under dark yet clearing skies, the menorah-lighting once again took place at La Plaza Republica Oriental del Uruguay on Buenos Aires’ central Libretador Avenue. As usual, the event was joined by dignitaries: The chief of cabinet ministers of Buenos Aires Horacio Rodríguez Larreta was on hand, and Israel’s ambassador to Argentina, Dorit Shavit, kindled the menorah.

“The menorah-lighting has become a central part of Chanukah for the Buenos Aires Jewish community at large, and 2,000 people attend regularly,” explains Rabbi Levi Silberstein, one of the event’s organizers. “This year, there was a big campaign to honor the 30th anniversary, and the crowd was double the size.”

A special logo to mark the anniversary was designed and a social-media campaign, which will last throughout Chanukah, was launched. As a 20-piece philharmonic orchestra played, a film with highlights of the last 30 years was shown, reflecting the great changes the Argentine Jewish community has seen in the last three decades.

Why does Grunblatt feel it so important to mark this milestone?

“Sometimes, an organization can make a successful event once and then let it become a part of the past,” he explains. “To do something on this scale every year—not for any political or financial reason, but simply to mark a Jewish holiday—is something that should be celebrated. This menorah event has had a great impact not only on Jewish life in this country, but on all of Argentina.”

Join the Discussion