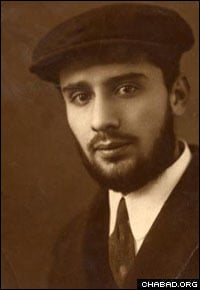

Rabbi Lipa Schapiro, a senior member of the central Chabad-Lubavitch rabbinical committee who mastered the study of Jewish law at the height of Soviet religious persecutions, passed away March 14 at the age of 97.

Born in 1912 in Kralevitch, Russia – the same city where his grandfather, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Schapiro, served as the community’s rabbi at the behest of the Third Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, known as the Tzemach Tzedek – Schapiro spent much of his childhood learning secretly from private tutors supported by his parents, Nochum and Raizel Schapiro. As Communism swept across Russia, living a Jewish life got progressively harder, but the family maintained a steadfast commitment to Judaism.

Schapiro’s mother was “very smart and clever,” he once said. “People used to consult her on various challenges in their lives.”

By the age of 13, Schapiro was seeking Jewish education elsewhere in the city of Ramen in one of the clandestine underground schools run by Chabad-Lubavitch. As was usual amongst the institutions, Schapiro’s school moved to a new location every six months to elude the secret police. Each time, the young student followed his teachers to Kremitchuk, Polatsk and Kharkov, as well as other places.

In Kharkov, students were forced by the authorities to disperse, and Schapiro returned home to Kralevitch. There, the town’s rabbi and scholar, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Dubrawski, noticed that the young man lacked a study partner and offered to help him in his Talmudic studies.

With Dubrawski, Schapiro was exposed to the breadth and depth of Jewish law, and one day, the scholar instructed Schapiro to respond to religious inquiries under his tutelage. For the two years of his apprenticeship, Schapiro acquired the tools and expertise that would later serve him well as a rabbinic advisor.

In 1937, Schapiro married Chana Vilenkin, the daughter of a ritual slaughter in Yekaterinoslav, known today as Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine.

War Begins

Schapiro’s studies with Dubrawski came to an end after neighbors reported on the pair to the Communists, forcing Schapiro and his wife to move to what was then Leningrad. The large city offered numerous opportunities to hide from the authorities, as well as employment for Schapiro, who took a position in a knitting factory to help support his family.

In Leningrad, Schapiro worked by day, and spent his night hours establishing and secretly teaching in the nascent Tiferes Bachurim yeshiva, a Chabad-Lubavitch institution that served young adults between work and university hours.

The experience revealed Schapiro’s inborn talent as a teacher, especially for students unaccustomed to the rigors of daily religious study, and for whom, given the official prohibitions on Jewish life, learning with the rabbi was their only Judaic outlet.

But Communism intruded once more when the secret police came knocking on the door of Schapiro’s classroom. The rabbi jumped out the back window, and spent the following three years wandering from city to city, never sleeping twice in the same place. Schapiro’s wife moved back to her parents' home, while the rabbi lodged in the homes of relatives, friends and strangers, and in synagogues’ attics.

The death of Nikolai Yezhov, one of the leaders of the secret police, provided some respite, and the relaxation of some official persecutions. Schapiro reunited with his wife, and they returned to Leningrad.

During the ensuing years, Schapiro occasionally visited Yekatrinoslav, where his wife’s father had forged a very close relationship with the city’s famed rabbi, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson and served as the only teacher of the rabbi’s son, the future Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory.

In later years, Schapiro – who was one of the last living people who knew the Rebbe’s father before he was exiled to Kazakhstan – shared his memories of the late rabbi, emphasizing the scholar’s unbending adherence to Jewish law even as the Soviets did all they could to quiet him.

Escaping Russia

World events separated Schapiro from his wife once more when the German Army began the Great Siege of Leningrad in September 1941. Chana Schapiro was vacationing with her family in Ukraine when the Germans cut Leningrad’s food supplies. Her husband, who had saved a small fortune of money, assisted anyone he could in funding their escape.

Finally, Schapiro escaped himself and set out on what would be a two-year search for his wife and her family, who stayed ahead of World War II by travelling east away from the advancing frontlines. In the Uzbekistan capital of Tashkent, where lax enforcement enabled the Jewish underground to flourish, Schapiro learned that his wife and family were in Mechatchkala. Weak with fever, he summoned them to Tashkent, where they reunited and settled.

In Tashkent, Schapiro utilized his prior work experience to become a manager of a local factory. He and his wife raised two children, and used Schapiro’s earnings to help many of their fellow Jews escape from the Soviet Union.

At the end of World War II, the family decided to join their fleeing brethren and pose as Polish refugees in order to escape the Iron Curtain. They journeyed to Lemberg, tore up all of their Russian identity cards, and from there reasoned that the safest time to cross the border would be on Shabbat.

Schapiro, knowing that one was permitted to desecrate the holy day in order to preserve his or someone else’s life, still strove to refrain from prohibited work. He dispatched his wife and children by wagon, whereas he opted to run the entire length of the long distance to the train station.

Jews in the Polish city of Krakow provided them safe transport through Czechoslovakia and on into Germany, where the Schapiros gained entry to the Poking Displaced Persons camp run by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in the American zone of Germany.

In the camp, Schapiro took up a leadership position and once again, delivered lectures in relative quiet. The family obtained visas to France, and settled there with thousands of other refugees. In Paris, he led the housing unit of the Lubavitch office in the city, earning a reputation for fairness in mediating disputes between neighbors. Although he planned on being in the French capital for six weeks, the family remained there for six years until 1953, when the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society procured visas for them to travel to the United States.

With dreams of being closer to the Rebbe in Brooklyn, N.Y., the family learned that they would instead be relocated to Cleveland, Ohio. When they arrived in New York for a stopover, after travelling by plane via Ireland and Canada, they received an audience with the Rebbe and expressed their wish to remain in Brooklyn. The Rebbe, though, advised them to continue to the American interior.

Creating a Chasidic Atmosphere

Settled in Cleveland, Schapiro filled the Jewish community’s need for a ritual slaughterer. Under the direction of the Rebbe, he also organized classes in Chasidic thought, and would teach students from the Telz Rabbinical College, an institution known more for its Lithuanian style of learning than for a Chasidic approach.

According to former students who took time out of their schedules to study under Schapiro, it was a perfect match.

“We used to go to the Schapiros’ to learn Chassidism,” said Rabbi Chaim Goldzweig, a veteran rabbinical field representative for the Orthodox Union in the Midwestern United States. “He would teach us, make Chasidic gatherings and would encourage us to grow in our Jewish life.”

Goldzweig said that the classes exposed the warmth of Judaism and led many to strengthen their religious observances. Schapiro’s students would later bring about a revolution in the Cleveland community by advocating higher standards of observance of kosher dietary laws.

Among his other accomplishments, Schapiro strove to ensure the availability of strictly kosher milk in the city, earning a nod from the Rebbe. When he once gave Schapiro wine to use at a Chasidic gathering in Cleveland, the Rebbe said with a smile that he should mix it with milk.

But it was his ability to mentor students that personally touched those who came through his doors.

“He had a straight way of thinking,” said Rabbi Dovid Helberg, rabbi of Bais Isaac Tzvi synagogue and school in Brooklyn. “Many came to him with questions in their studies and for advice in their daily life.”

On top of his hectic teaching schedule and communal duties, Schapiro spent his free moments advancing in his own studies with a slew of partners.

According to Helberg, local rabbis and Talmudic scholars at the yeshiva came to respect Schapiro as a Torah scholar in his own right. The rabbi, he added, “understood and respected all the various paths of the Jewish community in Cleveland.”

Schapiro especially formed a very warm relationship with the schools deans, Rabbi Mordechai Gifter and Rabbi Chaim Stein. Gifter passed messages through him to the Rebbe and would confide in Schapiro on Talmudic studies and other issues that came up in the school.

The Schapiros’ approach reflected encouragement they received from the Rebbe, who once told them that “the community needs to know that there are Chasidic Jews living in the city.”

Master of Compromise

During the High Holidays, Schapiro went to synagogues where there was no official rabbi or cantor. He once told the Rebbe in the 1950s about the effort, saying that it was taxing to pray with a crowd whose Jewish practice was lacking in the basics. The Rebbe responded with a question: “Is the fact that they are Jewish not good enough for you to pray with them?”

This guiding point of caring for every Jew regardless of his or her level of observance became a hallmark in the Rebbe’s approach to outreach, and led Schapiro to send the Rebbe a full report of his High Holidays activities year after year.

“Take every opportunity to speak inspirational words of Torah: after the reading of the Torah, during the meal after prayer services, between afternoon and evening prayers, etc.,” the Rebbe advised Schapiro. “However, the talks should be as short as possible.”

When the strength in his hands waned and he couldn’t hold his slaughtering knife properly anymore, Schapiro resigned his position. He again turned to the Rebbe for permission to move to New York, where he could open a factory with his brother in order to earn a livelihood. This time, the Rebbe gave his blessings.

As in Kralevitch, Paris and Cleveland, Schapiro was a natural leader in New York, where he got involved in rabbinic and communal work. Shortly after his arrival, he became the rabbi of the Empire Shtibel in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Crown Heights. Three times a week, he led a Talmud class attended by many local residents.

As a member of the Central Committee of Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbis of the United States and Canada, he frequently strove to foster compromise. Those who knew him said that even if he couldn’t get the competing sides in a case to work out their differences, he strove to gain their acceptance of his ruling, making sure that they walked away satisfied.

“He was very fair,” said daughter Raizel Goldberg, who took care of her parents during the last few years. “Even with my siblings, he was amazing at settling our fights, and we would all come out happy.”

“Rabbi Schapiro was confident in his opinion,” added Rabbi Nochem Kaplan, director of the Chabad-Lubavitch rabbinical committee. “He would never sway from what he understood to be correct. Even if he knew that his opinion was contrary to everyone else’s in the room, he did not mind voicing it.”

Rabbi Berel Levine, a scholar and author of many Jewish legal volumes, said that Schapiro’s experiences underlined his greatness.

“The fact that he had gained such great knowledge of the Talmud and the responsa of Jewish law while he lived under the Communist regime, points to his great mind and learning capabilities,” he said.

His Talmud class continued right up until his hospitalization in his last week of life.

“G‑d gave him mental clarity until his last day at the age of 97,” said Rabbi Moshe Bogomilsky, who served with Schapiro on various legal cases. “This shows that he had great merit.”

Schapiro was preceded in death by his son, Levi Yitzchak Schapiro, who passed away in 1990. He is survived by his children, Rabbi Sholom Ber Schapiro, Raizel Goldberg, Rabbi Yehuda Leib Schapiro, Rabbi Gavriel Schapiro and Rabbi Nochum Schapiro; and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Join the Discussion