As the 20th yahrtzeit (anniversary of passing) of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—draws near, print and electronic media have been awash with content devoted to his immense contributions to and influence on Jewish life in the 20th century and into the 21st.

As part of the broader relaunch of TheRebbe.org, two Chabad.org team members have crafted new works that explore an area that has been less accessible to the wider public—how the Rebbe’s Torah scholarship and philosophy were intrinsic to his life and leadership.

Chabad.org editor Rabbi Yanki Tauber recently completed the first section of an upcoming monograph, The Rebbe’s Philosophy of Torah. Chabad.org research writer and editor Rabbi Eli Rubin produced Scholar, Visionary and Leader: A Chronological Overview of the Rebbe’s Life and Ideas. Here, they discuss these new online works.

What is the primary motive and goal behind each of these new works?

Tauber: We’ve all seen many assessments of the Rebbe’s impact on the Jewish community and beyond as a leader and a visionary, but I felt that there could be more emphasis on his unique approach to Torah scholarship. What I set out to do is to try and demonstrate the underlying themes and ground-breaking approach that characterize the Rebbe’s prodigious output of Torah teachings.

For example, the section titled, The Divine and the Human in Torah, discusses the Rebbe’s approach to the human-Divine partnership that defines Torah. On one hand is the notion that every nuance of Torah is G‑d’s wisdom that cannot be altered. Yet our understanding of the written and oral Torah is very much the cumulative product of thousands of years of human creativity, too. I’ve tried to show how the Rebbe blends two seemingly disparate axioms together into a cohesive philosophy.

Rubin: The goal of Scholar, Visionary and Leader is to highlight some of the central events and ideas that together make him so uniquely influential, both in terms of activism and leadership, and in terms of scholarship and philosophy. The product is 28 articles, each one encapsulating a period of the Rebbe’s life and highlighting a key idea or theme that characterizes it.

The entry covering the years 1927 to 1932, for instance—a period during which the Rebbe attended the lectures of Erwin Schrödinger at the University of Berlin—provides an analysis of how the Rebbe used the new developments in quantum theory to articulate his approach to science and Torah.

Other topics include the Rebbe’s youth and upbringing in Yekatrinoslav, his marriage to the Rebbetzin, his approach to faith in the face of the Holocaust, his vision of America as a place of religious opportunity, his focus on empowering individuals, his efforts and policies vis-à-vis Soviet Jewry, and the responsibility Jewish people have to all humanity.

Is there one theme that you think characterizes the Rebbe’s life and ideas?

Rubin: The Rebbe’s communal policies and Torah scholarship are both marked by his vision of the Torah as a unified blueprint that illuminates everything. To my mind, what characterizes the Rebbe’s approach on every issue is his concern that the light of Torah continues to illuminate lives. It is therefore impossible to separate the Rebbe’s Torah scholarship and philosophy from his vision and leadership.

One thing that both Yanki and I keep coming back to is the theme of unity. Too often, unity is devalued; it’s turned into a cliché, or used to cover up differences and ignore them. But for the Rebbe, unity was the prism through which he saw everything. It was his mission to lay bare the singular essence that is the true core of all the complexity and dissonance of human experience. I can’t say I understand this; I don’t know if anyone understands it fully. But the more you study the Rebbe’s teachings and the more you study the Rebbe’s life, the more you see this.

There is one talk, later edited and published as an essay, On the Essence of Chassidus, in which the Rebbe definitively explained his unique vision of Chassidism and Torah. This is a text that is deeply profound, and the more you study it and restudy it, the more you see how it illuminates the entire corpus of the Rebbe’s ideas and teachings. More than explain what Chassidus is, he demonstrates how it works. He selects a Torah topic, analyzes it according to four classical forms of Torah interpretation and then shows you what happens when Chassidism discovers its essence.

In a similar way, it is very hard to explain why the Rebbe is so significant. But by presenting brief overviews of the Rebbe’s life and ideas, I am trying to show the reader something of the harmony that the Rebbe drew from the Torah into every area of life.

Can you offer some examples of how episodes or themes that you describe demonstrate the Rebbe’s unified perspective?

Tauber: The Rebbe’s approach to Talmud study can be described as a synthesis of the approach innovated by Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk with that of the Rogachover Gaon (Rabbi Yosef Rosen), with whom the Rebbe began corresponding as a teenager.

Brisk champions the understanding that fine lines can be drawn to differentiate laws and concepts that appear to be identical at the outset. On the other end of the spectrum, the Rogachover espouses the unity of Torah, teaching that a central unifying theme could be found in areas that appear to be completely unrelated.

The Rebbe drew from both. For example, he famously demonstrated how seven different disagreements between the schools of Hillel and Shamai all hinge upon a common, broader disagreement—and then went on to explain how each individual disagreement is unique.

Rubin: Two related examples come to mind. The first is the issue of science and Torah; the second is the issue of feminism and Torah. Even today, these issues remain extremely contentious and polarizing. What usually happens in these debates is that one person comes with one set of assumptions and another person comes with another set of assumptions, and each declares the other’s assumptions to be wrong. But the Rebbe didn’t do that; the Rebbe did exactly the opposite. The Rebbe actually put scientific and feminist assumptions to work in support of the Torah position.

What does this have to do with unity?

Rubin: It seems to me that the reason why the Rebbe was able to give scientific and feminist assumptions validity—without altering his vision of Torah in any way—is because the Rebbe believed that everything in the world stems from the unified core of Torah. In On the Essence of Chassidus, the Rebbe tells a story about his father-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak of Lubavitch: On one of his journeys, he encountered several people debating Torah’s view of various theories of social governance, communism, capitalism, etc. When they asked his opinion, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak said: “Being the ultimate truth and good, Torah includes all the good aspects of all the theories.”

The Rebbe believed that even things that are clearly wrong and contrary to Torah must have a core of truth upon which they stand. There are things that are true and good, and there are things that are distortions of truth and good. Inherently, it is only when their own truth is distorted that science or feminism can be misrepresented in terms that contradict Torah. Our job is to reshuffle things so that the good shines through. An article in this series is devoted to each of these topics, and I don’t do all the explaining I’ve done here. Instead, I just try to give a snapshot of the Rebbe’s approach, giving some perspective, but by no means the whole picture.

What are some of the sources that you drew on for your research?

Rubin: In addition to the Rebbe’s published works, including the many volumes of talks, correspondence and personal journals, I owe an immense debt of gratitude to the JEM (Jewish Educational Media) “My Encounter” team for the interviews they have conducted—and continue to conduct—with people who encountered the Rebbe at various stages in his life.

In addition to the historical corroboration of events from multiple witnesses and documents, and the many gaps that they have filled, JEM’s interview series also provides the very valuable element of human insight. You get to see how real people were touched in real ways.

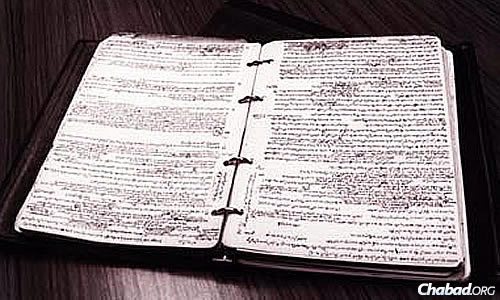

Tauber: My most primary source is the more than 200 published volumes of the Rebbe’s works: the talks and Chassidic discourses he edited, the many transcripts of his talks produced by listeners, the copious correspondence that has been published so far, and scholarly notations (reshimot) in his personal journals that came to light after his passing.

In addition, there are my own memories from the more than 20 years of the Rebbe’s farbrengens (gatherings) that I attended, starting as a child. Although the Rebbe was addressing Jewish scholarship of a very high caliber at these gatherings, everyone was there—men, women and children of all ages and backgrounds. Toddlers would be there sitting on their fathers’ laps. Everyone absorbed something on their level. Beginning at the age of 10 or 11, I began to retain significant ideas from the Rebbe’s talks, and that continued until 1992.

For the past 25 years, I have devoted a significant part of my working life to authoring treatments of the Rebbe’s teachings. To compile this work, I’ve drawn on the hundreds of articles I have written in the past. In a way, this is an attempt to draw it all together into a cohesive picture of the Rebbe’s unique understanding and application of Torah.

What are some of the most important things you hope a reader will take away from your work?

Rubin: My hope is that people will take these articles and run with them. They are all footnoted, giving the reader plenty of scope for further study, and there really is so much more on every one of these topics, and so many more topics besides. So I hope scholars and laypeople alike will be inspired to delve ever deeper into the Rebbe’s ideas, and try to emulate something of the way he lived and taught. Thank G‑d so many of the Rebbe’s talks and letters have been published. Especially insightful, but woefully understudied, are his personal journals from the years before he became Rebbe. JEM has also published many videos of the Rebbe’s talks and personal interactions. No one can say that there is not enough material. We all have a lot more to learn, a lot more to think about and a lot more to do.

Tauber: A better understanding of the Rebbe, of the Torah, and how Torah is the foundation of life.

Start a Discussion