“The life of a tzaddik,” wrote Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, “is not physical but spiritual,” consisting of “faith, awe and love” of G‑d. Accordingly, the passing of a tzaddik—a righteous person or holy man—from earthly life should correctly be viewed as the ascent of the soul from bodily constriction. The spiritual life of the tzaddik is now more easily and directly accessible to us, wherever we may be, precisely because that life is no longer mediated by the corporeal limitations of a physical body. As the Zohar says, “a tzaddik who departs is present in all realms more than in his lifetime.” A tzaddik does not die, but rather “leaves life for those who live.” (Tanya, Igeret Ha-Kodesh, Epistle No. 27)

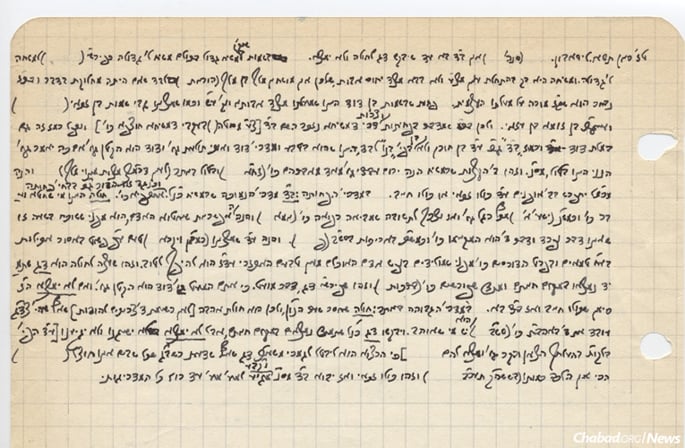

In the case of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—one material expression of leaving behind life for those who live can be found in three binders of autographic manuscripts that were found in the drawer of his desk shortly after his passing in the summer of 1994.

These were the Rebbe’s personal journals, penned between 1928 and 1950, in the decades before he took public leadership of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. With their publication under the Hebrew title Reshimos, it became possible to access his inner life more deeply than ever before. These were not conventional journals. The entries did not record mundane events. They instead captured what the Rebbe once described in a private letter to his father-in-law as the “the world of introspection . . . the world that is in my heart.” (Igrot Kodesh Harayats, Vol. 15, Page 78)

***

Several hundred people filled a Philadelphia auditorium on June 5 for a multimedia production and reading inspired by a selection from the journals penned by the Rebbe in the period directly before and during World War II and the Holocaust. “Maybe Alone, Never Forsaken” was produced and written by Bentzi Avtzon, and it was his fourth contribution to Lubavitch Center of Philadelphia’s annual event marking the anniversary of the Rebbe’s passing on the third of Tammuz, 1994. As Avtzon explained, he hoped to find a way “to bridge Chassidic thought and creative media,” and thereby to provide “a more engaging and more accessible glimpse into what the Rebbe was thinking in unthinkable circumstances.”

The Reshimos range across rabbinic and Chassidic literature with great breadth and cryptic brevity, and most people assume that they can only be made accessible to scholars. Yet Avtzon sensed that they also carry a poetic element—“a theme of persistent faith within the individual . . . the one last sanctuary in a world gone entirely dark.” In articulating that faith through his Torah musings, the future Rebbe held his inner world intact and focused on his personal responsibility as a servant of G‑d, whatever the circumstances. It was this sense of inner cohesion and unwavering responsibility that Avtzon wanted to share.

Heading to the venue, I perused a volume of Reshimos, and wondered how such dense and difficult material could be made accessible to a public audience. To me, it was their Talmudic complexity, mystical allusions and symmetrical attention to detail that made the Reshimos so compelling. Surely, all that would be lost on anyone unschooled in the rabbinic and Chassidic textual traditions?

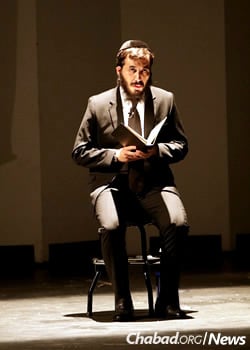

Several hours later, the audience watched Avtzon walk across the stage, a small black binder in his hand. He sat on a stool facing the audience and waited patiently as the stage lights went dark, obscuring him from view. On a massive projector screen, a black-and-white vintage reel began to play of children digging in some sand. As the shot cut to a wider angle, the iconic spire of the Eiffel Tower appeared in the background, viewed from the intimate angle of the most ordinary of street scenes. In swift succession, a series of clips immersed the viewer in the street life of Jewish Paris in the mid-1930s, complete with synagogues, kosher bakeries and rabbinic-looking Jews sporting frock coats and umbrellas. Then the film abruptly cut to a different view of the Eiffel Tower—this time dark and rainy, with the wind whistling ominously in the background.

As the stage lights came back on, Avtzon opened his binder and began to read:

In 1935, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson and his wife, Chaya Mushka, lived in a small apartment on Rue Boulard, a quiet street in Paris to the south of the Seine river. They had arrived here two years earlier, having escaped from Berlin shortly after the Nazi party had risen to power . . .

In his notebooks, we find an entry Rabbi Schneerson wrote during this time, notes for a speech he gave in the synagogue he frequented in the Jewish quarter, a little less than an hour walk from where he lived.

At this point, Avtzon stood and again began to read. Rather than a direct translation, Avtzon had reformulated the Rebbe’s thoughts in an aphoristic idiom that echoed the brevity of the Reshimos, amplified their poetic rhythm and abstracted their conceptual content from the cryptic complexities of rabbinic shorthand:

Chanuka. December, 1935. Paris.

Tonu Rabonon:

The sages of the Talmud questioned:

Mai Chanuka?

What is Chanuka?

Though they lived close to the time of Chanuka, still, they questioned . . .

. . In the dark of Exile, they questioned the holiday of Lights.

. . Said the sages, we celebrate a finding of oil, oil hidden beneath the stone floor of the Beis Hamikdosh, oil in a closed flask, sealed with the mark of the Kohen Gadol, the High Priest.

A closed flask.

Closed, fastened. And therefore pure.

So it is for a Jew. One who is fastened, one who is a Gan Na’ul—a garden reserved for G‑d alone—such a person, like a sealed flask, is forever pure.

(For the original entry, see Reshimos, No. 125.)

***

The full production lasted 50 minutes and followed a simple pattern: Vintage footage carefully edited to recreate the historical moment—the place, the time, the atmosphere—was interspersed with Avtzon reading from his reconstruction of the Rebbe’s journal. From the relative peace of the opening segment, viewers were soon thrust into the sudden mayhem of war, into the shattered streets of bombed cities and into the ramshackle encampments of weary refugees.

In the summer of 1941, on the Shabbat following Tisha B’Av—the day that marks the destruction of two temples and the terrible slaughter of the Jews at the hands of the Romans—the Rebbe, too, was a refugee. On that Shabbat, we customarily read a passage from the biblical prophet Isaiah in which he comforts the Jewish people ahead of the devastation to come. It was his reflection on this passage that the Rebbe shared with his fellow refugees and which he recorded in his journal. In Avtzon’s rendering:

Nachamu Nachamu Ami.

Comfort, comfort My nation.

A double comfort.

The midrash explains: The prophet Isaiah speaks this double comfort to a people suffering a double punishment

a double punishment for a double sin . . .

. . Ordinarily, reward and punishment from Above is in proportion to man’s deeds.

. . Ordinarily. When all else is equal, when man fulfills his obligation to G‑d, when man fulfills his obligation to this world.

But when man not only sins but sins in double, when man not only abstains but also destructs, transgresses, when all else is unequal, then man must reach beyond the world’s natural order, beyond, even beyond its spiritual orders.

And how does he reach beyond?

By confronting this unfathomable, incomprehensible moment, in which G‑d is hidden and sin is encouraged, by withstanding this test, knowing as he does that it is a test, that G‑d is like a father, is a father, who hides from his children only to evoke in them a feeling they never knew existed.

By confronting, by withstanding,

by remembering

that on the other side of this double suffering lies a double comfort.

(For the original entry, see Reshimos, No. 13.)

This is a different kind of theodicy. Evil is not explained away; neither is G‑d judged or absolved. Yet the capacity for evil—and the imbalance of that capacity over the capacity for good—is given coherence and purpose. Imbalance begets imbalance, and an imbalance of evil creates the opportunity for an overwhelming imbalance of good. Both evil and good, however, are given into the hands of humanity. It is up to each individual to raise himself out of the chaotic context of the historical moment. By transcending the natural order, by transcending the inexorable flow of malevolent circumstance, we transform a double measure of suffering into a double measure of comfort.

***

As Avtzon—who serves as creative director at yuvlaMedia, a boutique studio whose productions communicate Chabad learning and culture through film and music on stage and screen—told me the next day, he sensed a common thread that ran through these journal entries—a primal insight that illuminates what drove the Rebbe as a leader in the post-Holocaust era, and which continues to inspire all those who draw on the life that he has left us. The starkest and most explicitly introspective formulation of this insight appears in an undated journal entry that Avtzon nevertheless included, a key passage of which I translate here directly from the original:

There is nothing in the world—in the world of each individual except for G‑d and he. For all else are nothing but the means through which his service to G‑d shall be completed. And anything that is irrelevant to him in his service of G‑d, he does not know about it, for there is no thing or knowledge that is in vain, and all the world in its entirety—his world—is nothing more than a tool of use and a means, that through it you shall reach the purpose—the ultimate objective for which purpose he was created.

He must know that this is so also on the part of his fellow . . . and also in the world and knowledge of his fellow this is so . . .

(Reshimos, No. 44, emphasis in the original.)

In short, nothing can interfere with your personal obligation to G‑d, and yet everything you encounter must be incorporated into that relationship.

This is a strikingly powerful statement of individuality—a call to raise yourself out of the natural flow of history, to be the master of your circumstances. It is also a statement of uniqueness; the unique circumstances of your life set the distinct parameters of your unique mission, your unique relationship with G‑d and your unique path to personal fulfillment. Furthermore, it a statement of equality, for this is true of everyone: No one person is subordinate to the mission of another. Every individual must know that he or she is alone with G‑d. Every individual must say “the entire world was created for me.” (Cf. Talmud Bavli, Sanhedrin, 37a)

Fittingly, the event in Philadelphia concluded with an address by Rabbi Abraham Shemtov, chairman of Agudas Chassidei Chabad—the umbrella organization for the worldwide Chabad-Lubavitch movement—and head Chabad emissary in Greater Philadelphia. He recalled the events surrounding the original discovery of the Rebbe’s journals and the deliberations that resulted in their publication, and applauded yuvlaMedia for finding a way to make something of their content and significance so broadly accessible and resonant.

“There is one thing,” said Shemtov, “that the Rebbe always expected of us. That his words should not remain in the higher realms, in the abstract, in history and remembrance of the past. But his words should be translated into our lives. We should find them to be applicable and inspiring in our lives. Because here, we are here now, and the here and now depends on us.”

You can watch Rabbi Shemtov’s address below:

Join the Discussion