Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu Fogelman, an educator for more than 60 years, passed away on Aug. 30, just shy of his 89th birthday.

Throughout his long career in the Jewish school system, from which he never really retired, he was known for his warmth, wit and unending belief in the potential of each child. And while it’s not uncommon for children to remember their principals in less-than-glowing terms years even decades later, that was far from the case with Fogelman.

During Fogelman’s shiva, the weeklong traditional mourning period, a 70-year-old former student named David Farber stopped in. Farber recently celebrated the birth of a great-grandchild and had paused to think about the people who had impacted him over the years. Fogelman had undoubtedly been one of them, back when Farber was a student at the Lubavitcher Yeshivah at the corner of Bedford and Dean streets in Brooklyn. Although many years had passed and they had not kept up, hearing of Fogelman’s passing, Farber felt he needed to come to the shiva to share feelings.

As both a teacher and later a principal, Fogelman exuded a positive love for learning. But it hadn’t always been that way. In fact, he almost didn’t continue his yeshivah studies had it not been for a nudge in that direction from the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory.

Not long after his father’s untimely passing in 1945, Shmuel left the Lubavitch yeshivah in Brooklyn and went back to home to New Jersey to work and help his mother, while taking college classes at night. He still kept in touch with his old friends and would return to Brooklyn for holidays or special events on the Chabad calendar.

When the sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, passed away in 1950, Shmuel came to Brooklyn to attend the funeral. A little while later, his old yeshivah friend, Zelig Sharfstein, told him that Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s son-in-law and successor, the Rebbe, was very accessible and he should make an effort to meet with him.

During that first audience, the Rebbe asked his young visitor whether he studied Torah each day. Shmuel responded honestly, saying he did not. Between his daytime work and then ferrying into New York for night school, there just wasn’t any time.

“Then, the Rebbe gave me a mussar [stern] speech, but with love, with a smile, with kindness—you could hear it in his voice every single minute,” Fogelman recalled in an interview years later. The Rebbe impressed on him the importance of maintaining dedicated times for Torah study. At the end of the audience, the Rebbe expressed his hope that Shmuel was not upset by his words. “No, why should I be upset?” responded Shmuel. “It’s your job!” And the Rebbe laughed.

That interaction set Fogelman on a new path—one that eventually led him back to the yeshivah and into the world of education. It also marked the beginning of a long, warm relationship between the Rebbe and Fogelman. It was not only the content of the Rebbe’s advice—that he set aside time for Torah study each day—that impacted Fogelman, but the way the Rebbe had said it.

Focusing on the positive, encouraging and not berating, strict but kind, and always with a bit of playful humor, these became the hallmarks of Fogelman’s decades in Jewish education. Before returning to yeshivah, Fogelman had been accepted to law school, a career he did not ultimately pursue.

“I did not end up in law school, and thank G‑d, I had a better life than being a lawyer!” Fogelman said. “I had a life in chinuch [education], and that is much more important.”

American Boy With Russian Roots

Born on Oct. 2, 1929, in Brooklyn, N.Y., Shmuel was the third child of Chaim Elchonon and Chava Fogelman. His father, a native of Polotsk, today Belarus, had been a student in the Chabad yeshivah in the White Russian village of Lubavitch from 1905 to 1906, when he became subject to the Czarist draft. To avoid it, and with the blessing of the fifth Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom DovBer, Chaim Elchonon headed for the United States, where he arrived in 1907.

Chaim Elchonon did well in the New World, carving out a niche manufacturing men’s clothing. Yet he was still a yeshivah student at heart, described in the Yiddish-language Jewish Morning Journal as a “known clothing dealer and a fiery Lubavitcher Chassid.” Following the 1924 establishment of Agudas Chassidei Chabad of the United States and Canada as an umbrella organization for Chabad synagogues and activities in the country, Chaim Elchonon served as its vice president.

In September of 1929, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak arrived in New York to begin his historic first trip to the United States. It was towards the beginning of the visit that Shmuel was born. To the Fogelmans’ delight, the Rebbe agreed to serve as sandek, holding the newborn during hisbrit milah.

An account of the brit milah—held at the dedicated brit hall of the Brooklyn Jewish Hospital—in the Morning Journal, notes those who pledged donations to the Rebbe’s yeshivah in Poland during the festive meal held after the ceremony. Leading the list is Fogelman, donating $200—equivalent to nearly $3,000 today. He is followed by Anonymous, who also gave $200. Not wanting to upstage another prominent donor, Anonymous was, in fact, Fogelman as well.

Chaim Elchonon lived in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, and was a close friend, neighbor and business associate of Chaim Zalman (Chazak or Hyman) Kramer, then-president of Agudas Chassidei Chabad. When in July of 1930, towards the end of the Rebbe’s trip, he traveled to Washington to meet with President Herbert Hoover at the White House, Fogelman and Kramer both accompanied him, and can be seen in a well-known photograph together with the Rebbe.

Chaim Elchonon’s finances took a hit with the onset of the Great Depression, and when Shmuel was still a baby, the family moved to Asbury Park, N.J. Jewish education in America was still in its infancy at the time, and since there was no Jewish school in the area, he attended public school. Still, he would wake early each morning to study Torah with his father.

As Shmuel entered sixth grade, he was enrolled in Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, then under the leadership of the great halachic authority Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. Watching the venerable sage during prayers left a lasting impression on the young boy from New Jersey. It was something he would reminisce fondly about for decades to follow.

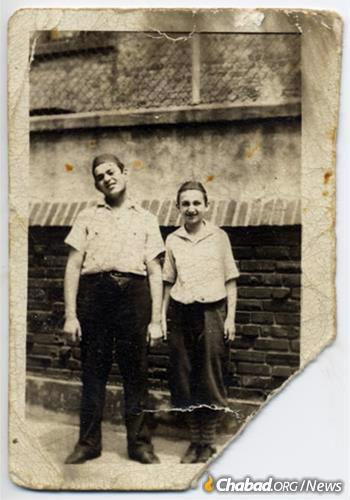

In 1940, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak was able to escape the Nazi inferno and make it to New York. He eventually settled in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, where he re-established his yeshivah on American shores. When Chaim Elchonon was told about the new yeshivah, he enrolled his sons, Nochum and Shmuel. Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak even sent Berel Baumgarten as his personal representative to Shmuel’s bar mitzvah. But after his father’s sudden passing in 1945, Shmuel went back to New Jersey. It was about six years later that he had his first encounter with the Rebbe, the one that changed so much.

Walking out of his private audience with the new Rebbe, Shmuel went back home to New Jersey. At first, he continued going to college—receiving his bachelor’s degree from New York University in 1953—and going to work. But a short time later, he was at his local synagogue and stopped in his tracks.

“I said to myself, you know, the Rebbe was right. I don’t know much, what kind of a way is this?” he recalled later. Seeing someone there who knew how to study Torah well, he arranged to learn Talmud with him once a week. From weekly sessions it grew to daily, and then on Sundays, when he was off from work, he’d head to Brooklyn to spend all day studying there. That summer he spent a few weeks at the yeshivah. When his mother saw how much he was enjoying his Jewish studies, she encouraged him to return full-time to the yeshivah in Brooklyn. Instead of going to NYU’s school of law, he did just that.

Although he was older than many of his fellow students, he studied hard, dedicating himself with a passion for the next four years.

One late Thursday night in the study hall, as he sat alone working through a particularly difficult tract of Talmud in a loud voice, he sensed someone watching him. He looked up and saw it was the Rebbe, gazing from the doorway with satisfaction. No sooner did he look up, and the Rebbe disappeared into a nearby office. He glanced at the clock and saw the time. It was 2 a.m.

“Maybe he had a little nachas [pleasure] that after he spoke to me, [and I responded] that’s your job, he saw what happened,” Fogelman mused years later. “Thank G‑d.”

With diligent study came responsibility. In April of 1956, Arab fedayeen—terrorists armed and trained mostly by the Egyptian government—entered the village of Kfar Chabad, Israel, and attacked the Beit Sefer Lemelacha vocational school, leaving five children and one teacher dead, murdered in cold blood while they prayed.

The Rebbe responded by dispatching 12 yeshivah students as personal emissaries to lift the spirits of the brokenhearted villagers.

Shmuel, by then ordained as a rabbi, was chosen as one of the Rebbe’s emissaries and charged as one of the group’s leaders. In addition to addressing large groups, his responsibilities included speaking to reporters and media outlets in the countries they visited along the way.

Lifetime in Education

When he returned to the United States he took on his first post, teaching sixth grade in the United Lubavitcher Yeshiva on the corner of Bedford and Dean streets in Brooklyn.

“We were a big group of boys, but he was able to handle us very well,” recalls Rabbi Sholom Ber Hecht, who was a student in that inaugural class. “He carried himself with dignity, which we caught on to. He was both demanding and encouraging at the same time.”

Among other innovations, Fogelman even introduced art into the curriculum. “It was quite an affair,” recalls Hecht. “We each had to put on an old shirt, get together our water and our paints, and then paint as he told us. He taught us about symmetry and appreciating art.”

In the winter of 1957, Shmuel became engaged to Shaindel Shimanowitz, who was born and raised in the underground Chabad community in the Soviet Union. The Rebbe urged the couple to keep their engagement period short and marry as soon as possible, even arranging a loan so that the wedding not be delayed for lack of funds. He also personally officiated at their wedding.

After his marriage, the Rebbe encouraged him to remain in the field of education. He did just that, and served as a principal in a number of schools. With the Rebbe’s blessings, in the late 1960s he received a masters in education from Yeshiva University, pursuing additional courses at NYU’s School of Education as well.

While having served for some time in positions in Pupa’s educational system and the Beth Rivkah girls school, it was the Lubavitcher Yeshiva that was his mainstay. He taught Jewish subjects and served as principal of secular studies at its old location on Bedford and Dean, helped start, administer and served as principal of the location on Crown Street in Crown Heights, and then worked at the branch on Ocean Parkway in Midwood, Brooklyn, for the last nearly two decades.

In addition to school, from 1965 to 1975 Fogelman directed Camp Gan Israel in Detroit. According to a 1973 article in the Detroit Jewish News, campers that summer went on strike demanding another week of sports and learning.

“Rabbi Shmuel Fogelman, the camp director, said he telephoned the Lubavitcher Rebbe ... to ask his advice,” reads the report. “The Rebbe ordered an immediate end to the strike and an additional week of camping for Gan Israel, said Rabbi Fogelman. To defray the expense, the Rebbe said he would pay half the cost, reflecting his concern for the education of Jewish children this summer ... ”

At times, Fogelman struggled to remain in the field of education, but the Rebbe always encouraged him to keep going, telling him that he should envision the future accomplishments of his students. “From amongst your students will emerge tzaddikim [righteous] and Chassidim,” the Rebbe told him. For the remainder of his life, he would derive immense satisfaction when he would hear from former students.

A case in point would be the visit he received about five years ago from a man he did not at first remember. The visitor confided that he had once, many years earlier, been a poor student, a trouble-maker of the worst kind, a kid whom everyone else had given up on. But not Fogelman, who had continued to believe in him. Now he was calling on his former teacher to let him know that he had just completed studying the entire Talmud for the third time.

“His entire thought was to raise up each student, to make them feel good and comfortable,” says Rabbi Shmuel Dechter, who worked alongside Fogelman at the Lubavitcher Yeshiva campus on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn for decades. “From morning to night, he was always thinking about the kids and what we could do for them.”

Dechter cites the example of a child whose parents sent him to the school one day without enrolling him or even informing the administration. “Rabbi Fogelman saw that the boy was nervous. He took him around, showed him his classroom and made the boy feel like a welcomed guest. Paperwork was irrelevant at that time. There was a lonely and confused little boy who needed to be cared for.”

Community Leadership

In the 1960s, Crown Heights began to change. That decade saw a sharp rise in urban crime rates sweep the country, which, combined with the postwar suburban boom and a practice called blockbusting—in which real estate agents, sometimes with municipal cooperation, used various scare tactics to urge city dwellers out—whole communities fled their previous neighborhoods. The demographic change in Crown Heights was particularly drastic, which went from a primarily middle-class, majority Jewish neighborhood in 1960 to 70 percent Caribbean American/African-American a decade later. Crime skyrocketed, and many Jews who had lived there for decades picked up and moved deeper into Brooklyn; others decamped for the suburbs. But the Rebbe insisted that he and his community would remain, encouraging others to do so as well.

The situation worsened in the 1970s, as New York became known as the ungovernable city. It was then that Fogelman became involved in local community politics, becoming an active voice for Crown Heights’ beleaguered Jewish community. In 1976, Fogelman became the first chairman of the newly founded Community Board 9, established to ensure that the Jews who remained in Crown Heights would have their voices heard.

While some argued that creation of the board split representation of the broader Crown Heights community in half, Fogelman passionately defended it—and the Chassidic community’s commitment to staying and not fleeing to the suburbs.

“Our spiritual leader, Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, said 10 years ago we must worry not only about our personal selves but about our community,” Fogelman told the New York Daily News at the time. “If richer people leave, the poor and the elderly remain behind. This is not right. We have decided to stay.”

Fogelman would also be appointed New York City youth commissioner by his friend and ally, Mayor Abe Beame.

But when all was said and done, it was his commitment to education that kept him going. Even in his later years, when he was unable to drive to school, he would ask his children, grandchildren or some of his non-Jewish neighbors to give him a ride. Since his office was right near the secretary’s, he would often be the first to meet children who had been sent out of class for behavioral issues. “How ya doing bud? What ails you?” was one of his signature greeting for the downcast youngsters, who knew they could count on the white-bearded rabbi for a listening ear, unconditional sympathy and some avuncular advice.

In addition to his wife, Shaindel, and sister, Naomi Gonsky, he is survived by his children, Rochel Ascher, Malky Freund, Faygie Shagalow and Rabbi Chaim Fogelman; grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Start a Discussion