The great American novelist Herman Wouk was a man who went against the grain. In a life and career that spanned the modern era, from World War I to iPhones, he stood out for his personal Orthodox Jewish observance, for the sense of mission he felt carrying the title “Jewish writer” and for the optimistic lens through which he saw the Jewish future. In all this and more, Wouk drew deeply from his intense, decades-long relationship with the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory.

Like many of his American Jewish contemporaries, Wouk—who passed away on May 17, just 10 days shy of his 104th birthday—was born into a traditionally Orthodox home. He grew up in the Bronx, N.Y., attended Columbia University and then got a job in show biz. After World War II broke out he enlisted in the Navy—an institution he would forever admire—and upon arrival back home published a war novel. His third book, The Caine Mutiny, brought him fame, fortune and a Pulitzer Prize. Yet Wouk bucked the popular trend; instead of abandoning tradition, he held steadfastly to the Jewish practices and beliefs of his parents, grandparents and ancestors.

In his life and art, Wouk—known as “Reb Chaim Zelig” at the Chabad-Lubavitch of Palm Springs, Calif., Jewish community he called home for decades—was an unabashedly proud practicing Jew. He started his day studying Jewish texts and closed it with a regimen of Talmud. In his work, including novels such as Marjorie Morningstar, he allowed characters to struggle with faith—not by mocking it, but by taking seriously the intricacies of observance. Instead of writing off religion, he allowed its transcendent beauty to touch and move his characters, and through them, his readers. When fellow novelists and critics took unkindly to this, he simply brushed off their critique.

He would remain “one of the few living novelists concerned with virtue,” his biographer, Arnold Bleichman, told the Palm Springs Desert Sun when Wouk turned 100.

Wouk was already a popular and successful novelist when he became a playwright, adapting his best-selling The Caine Mutiny into a Broadway play and later a movie. But even amid the nonstop world of Broadway, Wouk would disappear as Shabbat approached, “leaving the gloomy theatre, the littered coffee cups, the jumbled scarred-up scripts, the haggard actors, the shouting stagehands, the bedeviled director, the knuckle-gnawing producer ... and the dense tobacco smoke and backstage dust” for home. There, he would join his family at “a splendid dinner, at a table graced with flowers and the old Sabbath symbols: the burning candles, the twisted loaves, the stuffed fish, and my grandfather’s silver goblet brimming with wine.”

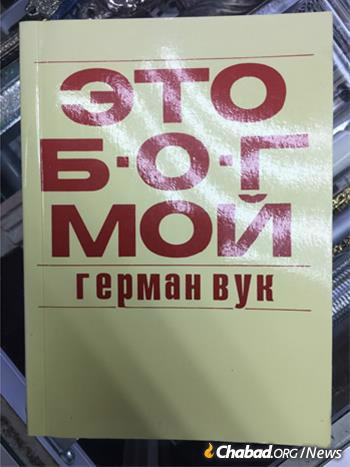

Wouk wrote these words in another book, This Is My God, which he composed in response to an offhand question by a Jewish friend asking him if he knew of any educational Jewish reading material. This Is My God, with the later added subtitle of The Jewish Way of Life, became an invaluable resource for non-Jews seeking to understand Judaism and had a revolutionary impact on Jews from all backgrounds.

In it, the writer turned his pen to explaining the Jewish faith in a relatable, down-to-earth way. It proved unexpectedly popular, was reprinted numerous times and translated into many languages, becoming a basic guide and reference book for anyone interested in authentic Jewish practice. In the Soviet Union, where decades of state-sponsored oppression had rendered its millions of Jews lacking basic Jewish knowledge, it became a wildly popular manual for the spiritually thirsty population, offering them a foundational Jewish education.

Wouk dedicated This Is My God to his grandfather, Mendel Leib Levine, who had served as a rabbi in Minsk, and later New York and Tel Aviv.

“From my [maternal] grandfather I caught an enthusiasm for learning, and a simple unashamed love of our faith,” Wouk wrote in a 1967 letter. “[He] was a Lubavitcher who studied ... in the Chabad tradition of knowledge joined with piety.”

This steadfast enthusiasm and love, as well as the moral backbone that it implied, never left him. In a career that saw him write nearly two-dozen books, including The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, Inside, Outside, The Hope and The Glory (he maintained a steady work regimen until the end of his life, publishing his latest book, Sailor and Fiddler: Reflections of a 100-Year Old Author, in 2015),he candidly invoked the moral choices facing humankind, spoke with clarity on the existence of good and evil, and emphasized that an individual’s thoughts, words and actions do indeed matter.

Wouk’s own steadfast Orthodox Jewish observance combined with his stature served as an example for his brethren and brought Jewish practice into the public eye. Like the time in 1955 when Wouk made an appearance in the New York Post’s “Lyon’s Den” gossip column—not for scandal, but because the governor of Maryland had made sure the full dinner served at a state function attended by Wouk would be kosher. Later, throughout the decades that Wouk lived in Palm Springs, he gave a weekly Shabbat morning Chumash class at the Chabad House and taught Mishnah on Shabbat afternoon. He also maintained numerous regular Talmud study partners, and when weakness forced his classes to relocate to his home, continued his study sessions via Skype.

“His Torah study, his Jewish practice, that’s who he was,” explains Rabbi Yonason Denebeim, director of Chabad of Palm Springs and his longtime rabbi and friend of many decades, who officiated at Wouk’s modest funeral. “He was a gifted storyteller through his words, but that was ancillary to who he was, he was a Jew. The medium was the writing.”

City Boy and the Zeide

Chaim Aviezer Zelig (Herman) was born on May 27, 1915, to Abraham Isaac and Esther Shaina Wouk. He and his siblings grew up in a Bronx fourth-floor walk-up, and as their parents hailed from White Russia, the family prayed at the neighborhood’s Minsker shul, where Wouk’s bar mitzvah was held. His parents were Orthodox Jews, religious but working hard to fit in with American life. Shortly after his bar mitzvah, Wouk’s maternal grandfather, Rabbi Mendel Leib, arrived from Russia, an event that stayed with the future author for the rest of his life.

“It was a Sunday” that the family went to greet the man they all knew as Zeide, Wouk recalled at a 1972 event held in Minnesota in honor of the Rebbe’s 70th birthday. “The boat arrived on Saturday and my grandfather wouldn’t leave the boat [due to his Shabbat observance]. The captain had never heard of such a thing, but my grandfather said, ‘I’m sorry’—you know, in his Yiddish—‘I’m not leaving the boat.’ ”

Zeide Mendel Leib stayed on the boat until after Shabbat was over, disembarking on Sunday morning.

“That was how Lubavitch came into my life,” explained Wouk. “When my grandfather came he brought a whole different attitude into our lives … What he said was in his action. There is nothing more important than being a Jew. Nothing.”

After graduating from high school, Wouk set off for Columbia University, majoring in comparative literature and philosophy, and beginning his literary career by writing a campus humor column and editing a college humor magazine. For a short few years around and after college, he tested the waters of secular life, before returning to Jewish practice. After graduating, he got a job as a radio gag writer before landing a position in 1936 as a staff writer for the then-popular radio comedian Fred Allen.

Wouk enlisted in the Navy after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and was eventually posted in the Pacific on the USS Zane, an old World War I minesweeper that would serve as a base for his fictional USS Caine.

His mother, Esther, told her midshipman son that there was no way he was going off to war without first receiving a blessing from the Lubavitcher Rebbe. This was 1943, and his recently widowed mother took him by subway all the way down to the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, where the two had a private audience with the sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory.

“The [sixth] Rebbe told him he should be especially careful with tefillin,” recalls Denebeim, who together with his wife, Sussie, befriended the Wouks when the author and his wife settled in Palm Springs and began attending Chabad on a daily basis. “The Rebbe told him that even though during times of emergency and war one was allowed to be more lenient doing practical mitzvahs, Wouk should nevertheless be careful with tefillin.”

Wouk would recount the details of the audience in The Will to Live On, describing Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak as a “gentle personage of imposing presence, recently escaped from Nazi-ruled Europe after a harrowing ordeal of Soviet imprisonment,” remembering how he “received us with grace, and we conversed in Yiddish, his voice weakened by asthma to a near-whisper. As I left, he gave me a blessing and with it a dime …”

Wouk held onto Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s dime throughout his years in the South Pacific and donned tefillin daily. He spent most of the war on the Zane doing the hazardous work of clearing mines before being transferred, in January of 1945, to the USS Southard, where he became the executive officer. Aboard the Southard, which had earlier survived a kamikaze attack, Wouk became the “bad cop” rule enforcer to the captain’s “good cop,” earning the enmity of those reporting to him.

The Pacific war ended in August. A month later, on Sept. 17, just as Wouk was about to become captain of the Southard and conn the ship back to Brooklyn, they were hit by a typhoon at Okinawa. Somehow—“miraculously,” Wouk would emphasize on numerous occasions—they managed to save everyone aboard. The ship was later declared lost.

Once ashore the next morning, everyone started “showing great deference to him”—calling him “Lieutenant Wouk”—“and he felt really strange about it” since he hadn’t been very popular with the men previously, says Denebeim. “He went to his chief petty officer and asked him what’s going on?

“You saved everyone on the boat,” came the reply.

“What?!”

“Not you! The black boxes you wore on the bridge every day!”

Wouk recalled the day clearly because it was also Yom Kippur, and he hadn’t eaten a thing. When the Southard was struck, Wouk rescued two things: the precious tefillin that Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak had asked him to wear daily and the draft of his first book, Aurora Dawn.

For the duration of his life Wouk had a special affinity for the Book of Jonah, the haftorah read on Yom Kippur. It tells the tale of a man nearly lost at sea and the doomed city he helped save.

What Makes a Jewish Writer?

Wouk married Betty (Sarah) Brown in 1945, with the couple having three children and remaining married for more than six decades until her passing. His debut novel, Aurora Dawn, published two years later, and was followed by City Boy. It was his third book, however, The Caine Mutiny, that brought him overwhelming success. In it, Wouk paints a picture of the Caine’s captain, an imperious and paranoid man whom some of the men fear will lead them to a watery death. Instead, they forcibly relieve the captain of his duties by exercising the little known Articles 184, 185 and 186 in the Naval Regulations. The propriety of their actions goes unchallenged for the duration of the book, before Wouk leaves the reader wondering whether the righteous mutineers may have gotten it all wrong.

Less ambiguous were his epic war novels, The Winds of War (1971) and War and Remembrance (1978), which tell the tales of the non-Jewish Henry clan and the Jewish Jastrow family. The combined nearly 2,000 pages, which Wouk saw as his life’s “main task,” paint an intricate picture of a world at war and brought the horrors of the persecution of the Jews in the Holocaust home to generations of readers. The Winds of War ends off with Natalie Jastrow, a young American Jewish woman stuck in Europe with a newborn baby in tow, blocked from escaping by German Nazis, Italian fascists and American bureaucrats.

“I’m beginning to feel like a Jew,” Natalie tells her uncle, a renowned academic who’d strayed far from his Jewish roots. “Oh?” he replies. “And I’ve never stopped feeling like one. I thought I’d gotten away from it. Obviously I haven’t.”

One of the novel’s countless readers was Vivi Deren, then a young Chabad emissary on campus in Amherst, Mass. Wouk was practically mishpachah, or family, with Deren’s parents (and Denebeim’s in-laws), Rabbi Zalman and Risya Posner, the Chabad emissaries in Nashville, Tenn., and the author would stay at the Posner home during his frequent visits to the city, where his nephew and family lived. One afternoon on the eve of Shavuot during the gap years before War and Remembrance came out, Deren was on the phone with her mother, who told her that Wouk was staying with them for the holiday.

“I said, ‘Please ask him what happens to Natalie?’ ” Deren remembers.

“Say tehillim,” came Wouk’s reply. It would seem that he still did not know whether his protagonists would perish together with their brethren.

When War and Remembrance finally came out, Wouk revealed that Natalie and her baby boy do indeed survive. Yet her uncle, Dr. Aaron Jastrow, a professor and writer who it is learned had become an apostate years earlier, does not. In the Nazis’ hands, the elder Jastrow returns to the faith of his fathers, begins donning tefillin, teaching Talmud and documenting his path to repentance in a manuscript he titles A Jew’s Journey. The elderly man dies in the gas chambers with the hallowed and holy words Shema Yisrael, “Hear, O Israel,”on his lips.

“I have experienced a strange bitter happiness in Theresienstadt that I missed as an American professor and as a fashionable author living in a Tuscan villa. I have been myself,” Jastrow writes in his final entry. “ … I was born to carry that flame.”

This Jewish flame, this light, permeated Wouk’s work. When Natalie Jastrow is finally reunited with her young son, Louis, she rocks him back and forth and begins singing to him in Yiddish:

“Dos vet zein dein baruf,” she sings, “Rozhinkes mit mandlen—”

“Almost at the same moment,” writes Wouk describing the scene, “Byron and Rabinovitz each put a hand over his eyes, as though dazzled by an unbearable sudden light.”

Wouk’s inner need to communicate the “sudden light” of a Jewish mother singing Rozhinkes mit mandlen, or a Talmud class in Theresienstadt, made him stand out.

While audiences scooped up his books and made him popular, critics launched attacks, citing his popularity as proof that he was a second-rate writer. Worse, in their eyes, was what they saw as his simplistic, old-fashioned morals.

“He writes out of a strong sense that Jewish life… can only disintegrate and wither away if it ventures beyond the moral and spiritual confines of a Judaic bourgeois style,” wrote one critical reviewer of Marjorie Morningstar.

And yet, Wouk held his ground.

“Among Jewish writers of the day I remain odd man out in point of view, of that I am well aware,” he wrote. “In some of them I think I discern rueful second thoughts about religion, but any relevance of eschewing lobsters to the grand question of man’s fate [as Wouk pondered in Marjorie Morningstar], in a vast baffling universe, may well seem to them a persisting petty absurdity. On that I have had my say in This Is My God, where I lay out my cards face up … ”

Jewish Survival

Wouk’s primary concern, he said, was the existential question of the survival of the Jewish people in a modern, post-Holocaust world. “That’s the way I am,” he told the Minnesota audience in 1972.

Wouk shared the overwhelming concerns of Jewish leaders about intermarriage, assimilation and basic lack of Jewish knowledge affecting American and world Jewry. “Leaders fear threat to Jewish survival in today’s ‘crisis of freedom,’ ” cried the famous 1964 Look magazine cover story ominously titled ‘The Vanishing American Jew.’ Wouk agreed: “I think the Jewish people is in danger—in mortal danger,” he said. From where, Wouk asked his audience as much as himself, could one derive faith in the Jewish people’s apparently bleak future?

How did Wouk end up so resolutely and positively portraying not only the inner light of Jewish life and practice, but his underlying optimism?

Wouk, a man who committed millions of words to print, was ironically also a man of few words (The Washington Post once called him “the reclusive dean of American historical novelists”). Yet on occasion, including at the Minnesota gathering, he allowed glimpses into his inner world.

“The Rebbe has that faith [in a bright Jewish future],” Wouk said in reply to his own query. “I think that the Rebbe is an inspired Jew, perhaps the inspired Jew among us,” he explained. The Rebbe “looked me in the eye and said it was so ... And so it is the truth.”

Over a period of many decades, Wouk enjoyed a deep and private relationship with the Rebbe, seeking and receiving his guidance, direction and encouragement. In 1972, on the occasion of the Rebbe’s 70th birthday, Wouk came to the Rebbe’s farbrengen gathering in Brooklyn as the personal representative of U.S. President Richard Nixon. Bearing a letter of greeting from the president, he had a private audience with the Rebbe (forcing then-Israeli ambassador to the United States Yitzhak Rabin to wait his turn). Then, in a period of just a few days, Wouk flew to both Minnesota and Los Angeles to speak at local gatherings celebrating the same event.

Mission

Wouk maintained a lengthy correspondence with the Rebbe and visited him numerous times for private audiences, cherishing the advice he got from the Rebbe about his literary work (they discussed his books in detail). But it was the Rebbe’s positive outlook on the Jewish condition and his urgent work to make it so that he would recount most often, recalling how during one of those audiences the Rebbe had negated the nay-sayers predicting doom. “The American Jewish community is wonderful,” the Rebbe told Wouk. “While you cannot tell them to do anything, you can teach them to do everything.”

The Rebbe didn’t miss an opportunity to encourage the author to keep writing in ever more consequential ways, to keep impacting and to keep doing more for the good of the Jewish people.

In a brief interlude during a 1975 farbrengen Wouk attended in Brooklyn—during which the author vigorously sang and clapped in rhythm with the crowd—Wouk joyfully reported to the Rebbe (in Yiddish) that his Israeli publisher had translated and published not just a novel of his, but a serious book on Judaism, This Is My God, and added that a special low-priced edition had been printed for the benefit of the soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces as well.

The Rebbe was happy to hear this, but then reminded Wouk that his work was not done. “It’s needed in America as well,” the Rebbe added. “Don’t forget the Jews in the United States!”

(This Is My God was also translated into Russian by Professor Herman Branover, a Lubavitcher Chassid and scientist who directed the Shamir organization, which worked on behalf of Soviet Jewry in the USSR and abroad. Branover’s translation of Wouk’s book made its way clandestinely into the Soviet Union, where it had a revolutionary impact.)

In a 1985 letter Wouk addresses to the “Revered Rebbe,” he concludes by saying “it remains for me to thank you for your too kind words about my very modest acts in [the] field [of Jewish education], and to welcome your blessings with profoundest gratitude.”

The Rebbe would not hear of it. “I must challenge this self-assessment,” the Rebbe wrote back, “on the ground that the record speaks for itself. Moreover, in wide segments of Jewry, especially among American Jews, the impact of your ‘modest acts’ strikes deeper and wider than similar acts of a Rabbi or Rebbe (myself included) could attain, for obvious reasons.

“For the sake of a mutual consensus, I am prepared to accept your claim of ‘very modest acts’—in a relative sense, in terms of your potential and future acts, which will dwarf your past accomplishments by comparison ... ”

The Flame

Attempting to illustrate the Rebbe’s effect on his life, along with the unique role he plays for the Jewish people at large, including his seemingly endless font of optimism despite insurmountable odds, Wouk once again reverted to the metaphor of a flame.

“Judaism’s fire has burned very low in our century. It burns low not only in America, and it is not only almost out in the Soviet Union, it burns low in Israel too,” Wouk explained to his Minnesota audience. “But an ember has always burned on the underside of the black log, and time after time in our history, at unexpected moments, a flame has leapt up, and on that flame we have piled ourselves and created a new blaze.”

The Lubavitch movement, Wouk said, is the “red ember on the underside of that ... smoldering log of Judaism ... ,” and the Rebbe “is the flame.”

Moved in this way by what he saw as the Rebbe’s vital role in the very survival of the Jewish people in the modern era, Wouk spoke passionately to audiences large and small, from Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia to London, about Lubavitch’s dynamic standing on the Jewish landscape. “In the thundering footsteps of the young Chabad Chassidim I did not hear the voice of the past,” Wouk told a Los Angeles audience in late 1972. “This is the life of Judaism and this is the future of Judaism. It was the voice of the future.”

It was not only for others. Early on, Wouk formed a deep working and personal relationship with the Rebbe’s emissary, Rabbi Avraham Shemtov, executive director of American Friends of Lubavitch, who became a personal confidant.

Wouk prayed at Chabad of Palm Springs, supported it, gave classes and lectures there, and considered its rabbi, Rabbi Yonason Denebeim, his own. They were friends, and Wouk on occasion wrote about Denebeim and his admiration for him. Denebeim, in turn, regularly spent hours in study and conversation with his famous congregant, whom he described as his “surrogate father ... for 40 years,” while fiercely guarding the writer’s privacy on his behalf. Wouk regarded Denebeim’s children, who continued to visit and study with him at his home until the end of his life, as if his own.

“Mr. Wouk was a special human being,” says Rabbi Denebeim. “Where many artists become defined and thus limited by their art, he shined beyond those limitations, a quiet lamplighter.”

Faith

“Faith,” Wouk once explained, “is belief in what cannot rationally be justified. It’s a knowledge that goes beyond logic.”

Wouk exuded this faith. In a 1968 talk Wouk gave in Philadelphia, he recalled visiting the Soviet Union two years earlier with his wife, where among the old, bent Jews he prayed with at the Choral Synagogue in Leningrad, he was surprised to also meet a young man—much too young to fit in with the others. The young man wore a modern suit but also sported a beard. Wouk asked him what he was doing there, and the latter responded he was a Lubavitcher Chassid from Riga and was there to ask Wouk to send a message to the Rebbe on his behalf. Although he told Wouk his name, the author forgot it over the duration of the ensuing trip.

“I am giving the Rebbe his message now,” Wouk told the audience in Philadelphia. “The Rebbe surely knows who he is. He is alive and well, his children are growing up as Chassidim, and he sends the Rebbe his love.”

Wouk often reflected on the Rebbe’s vision for world Jewry and the effect it continued to have even after the Rebbe’s passing in 1994, expressing a measure of this in a short note he wrote to author Joseph Telushkin following publication of the latter’s best-selling biography, Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History.

Telushkin’s book, Wouk wrote, was “the truth, simply and ably told, about a great man, a Jewish 20th century teacher and leader. ... The man emerges as himself, in all his simplicity and majesty. ... He will live on, I think, as his work lives on, and steadily grows in impact.”

What Makes a Lubavitcher?

In 1978, Wouk sent the Rebbe a copy of his then-new book, War and Remembrance. The book was dedicated to his eldest son, Abraham Isaac (“Abe”), who had tragically passed away years earlier in a childhood accident, and Wouk inscribed on the title page the prophet Isaiah’s words, Bila Ha’Moves Lo’Netzach, or “He will destroy death forever.” The Rebbe replied by thanking him for the book, noting the beautiful dedication and stating that he hoped to have the chance to go through the 1,039-page book at a later date. At the conclusion of the letter the Rebbe did, however, take issue with Wouk’s oft-repeated description of himself as an admirer, but not an actual member of, Lubavitch.

“In the estimate of many, myself included, you have been a Lubavitcher for quite some time,” the Rebbe wrote. “For as you surely know, being a Lubavitcher does not come by virtue of a formal membership card, or membership dues or anything like this, but to do what a Lubavitcher does: to spread Judaism with Ahavat Yisrael ... ”

Herman Wouk was a successful man, winning awards, selling many millions of books and the movie rights to his creations, all the while holding strong in his convictions. He studied and taught Torah not as a layman, but as a scholar, once calling himself “a Jew of the Talmud.” And he was, above all else, a lover of the Jewish people.

But he was not transient; he did not rest on his laurels. Wouk spent his nearly 104 years on earth on an upward journey, both personal and professional, taking him from skeptic to optimist, from defender of the faith to forward-looking emissary. Recognizing the slumbering embers deep in the log of American Jewry, he sought the flame, to warm himself and draw energy from it. Then he marshalled his immense talents in its service to help it grow into a roaring fire.

In addition to his son, Abe, Wouk was predeceased by his wife, Sarah, in 2011. He is survived by his children, Naftoli Hertz and Yosef Yitzchak; in addition to grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Join the Discussion