As a young man and already an accomplished Torah scholar, Rabbi Mordechai Burg felt he needed something more. “I was studying Talmud and the deep, analytical commentaries, but it was dry,” he recalls.

The dean of his yeshivah—Lander College’s Beis Medrash L’Talmud—Rabbi Yehuda Parnes, suggested that Burg begin exploring the world of Chassidic philosophy. For Rabbi Parnes, a disciple of the Lithuanian, non-Chassidic disciplines, “this was a radical departure from the yeshivah’s usual approach,” explains Burg.

Burg began to navigate the vast waters of Chassidic teachings, quickly finding that the “clearest and most systematic guide” to Chassidic life and thought was the Tanya, the foundational text of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement penned by its founder, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. Known also as the Alter Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman was a leading student of Rabbi Dovber, the Maggid of Mezritch, and a preeminent authority on both Jewish law and mysticism.

At the direction of the Maggid—who had succeeded the Baal Shem Tov, founder of the Chassidic movement—Rabbi Schneur Zalman authored what became universally known as the Shulchan Aruch HaRav, an extensive guide to Jewish law and tradition. At the same time, he began expounding on his predecessors’ core ideas by developing his Chabad Chassidic philosophy, a comprehensive intellectual framework for understanding and revealing the unity of G‑d in the world, and in the thought, speech and actions of each individual. The Tanya does more than lay this framework out on the theoretical level. It is also a practical guide, empowering people to negotiate the emotional and intellectual challenges that might otherwise prevent the lofty ideals from being realized in human life.

Today, Burg is principal of Yeshivat Shaarei Mevaseret Zion, on the outskirts of Jerusalem, which he describes as a “modern-Orthodox yeshivah that values what Chassidut has to offer.” Several years ago, the faculty opened a new class in the yeshivah: A select group of boys would devote two hours in the afternoon to the study of Tanya, taught by Burg. His classes gained a worldwide reputation and are now popularly streamed on several websites.

The key ideas introduced in Tanya, Burg tells Chabad.org, are eye-opening. “The idea of dirah betachtonim—that we are tasked with making this corporeal world an abode for G‑dliness—that’s fundamental for these boys. What will their Yiddishkeit [Jewish identity] mean to them when they leave the yeshivah and enter into the real world? Tanya teaches that we can bring G‑d into the world, anywhere,” he explains.

He further notes that while other schools of thought emphasize spirituality’s dissonance from the material, Tanya raises man to a higher plane and, simultaneously, “brings G‑d down into this world. It’s actionable.”

Dr. Lee Slavutin, an entrepreneur and retired physician who teaches a Tanya class at the Carlebach Shul on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, agrees. “The way the Alter Rebbe begins chapter one is earth-shattering. A normal book begins with a lengthy introduction, but he goes straight in, quoting the Talmud: ‘An oath is administered to him [before birth, warning him]: ‘Be righteous and be not wicked … .’ ” That opening line, says Slavutin, “addresses a fundamental subject: What is a person’s mission? The author gives his student the knowledge that goes to the core of things, to know that G‑d directly gives us each a mission from day one—the soul makes an oath—that’s very empowering.”

A “chance” 1998 encounter Slavutin had en route to his first visit to the Ohel, the resting place of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—led to a 10-year-long, one-on-one study partnership with a Chabad rabbi, during which Slavutin learned the entire book in-depth. “Looking back,” he reflects, “I don’t think there’s a better way to do it. It’s hard to learn it on your own initially.”

Growing Popularity in Person and Online

Because studying the Tanya for the first time is best done with a teacher, study groups like Slavutin’s and Burg’s have sprung up in synagogues and communities around the world. Additionally, dozens of audio and video classes are available on Chabad.org, and many use Kehot Publication Society’s Tanya with commentary.

Tanya’s growing popularity is a testament to a new generation of spiritual seekers, says Hindy Pruss, who leads a Tanya study group on Zoom for women at the Palm Beach Synagogue in Florida. “There’s a thirst for truth and connection to G‑d,” she says. “People have a soul they have to nourish; there’s a G‑dly soul that yearns to connect. It’s a search for emet, truth. A Jewish person is innately on that quest, and you can see it, it’s real. The Tanya resonates with them.”

Rabbi Moshe Scheiner, the synagogue’s senior rabbi, says the women have really connected with Tanya. “There’s something particularly special about how the women come together for this and delve so deeply; it’s inspiring and transformative,” he says. “Women are more spiritual than men.”

Pruss’s class, in which scores regularly participate online each Tuesday, began last Chanukah when she was visiting the Palm Beach Synagogue and struck up a conversation with community member Lisa Schreier.

Schreier opened up to Pruss and spoke of her difficulties feeling connected with G‑d. “We got into a deep discussion, and I asked her if she’d ever learned Tanya before,” recounts Pruss. Schreier wasn’t familiar with the Tanya but set up a weekly study session with Pruss (who lives in New York) over Zoom. The next time Pruss visited Palm Beach, Schreier’s friend found out about the class and asked to join. “Then, by word of mouth, it evolved into this group that meets every week; it’s taken on a life of its own.”

“Tanya has had a profound impact on my life,” says Schreier. “What we learn we carry with us throughout the week. For me, it helped me tap into my connection with G‑d. I always had a spiritual side, but I never knew how to connect with it.”

Tanya, she adds, is very relatable. “There’s a misconception that people have, ‘I’m not religious, so I’m not as holy.’ Tanya teaches that a Jew is a Jew is a Jew. We all have an animalistic soul and a G‑dly soul, and you do regretful things in your life. But it’s all human, and there is teshuvah (repentance, or literally, return).”

Unprecedented Boost in Study After Rebbe Calls for Printings Worldwide

One of the most popular commentaries on Tanya, Lessons in Tanya, was written by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg in preparation for his classes on the Yiddish radio station WEVD, which he began delivering in 1960. The Rebbe, who recognized the great significance in the new reach of modern technology, reviewed Rabbi Wineberg’s drafts with his own incisive and authoritative pen, thereby providing illuminating insights into the text—uncovering the layers of depth in the Tanya in so very many previously unknown ways. The beautifully and lucidly explained text, now replete with thousands of the Rebbe’s edits and glosses, was subsequently published in Yiddish, Hebrew, English, Spanish, Portuguese, French and Russian.

The radio classes, meanwhile, introduced entirely new audiences to the Tanya’s insights and life tools, and heralded a proliferation of Tanya study.

While the number of Tanya classes worldwide grew steadily each year, they began skyrocketing in 1978 and continuing throughout the 1980s, following the Rebbe’s call for the holy book to be printed in every locale around the globe where Jews reside.

The Rebbe explained that when a Jew participates in a local Tanya printing or even hears about an edition printed in his own city, it will pique their interest, and he or she will want to know what the book is all about. He taught that this was a key element in the quest to bring the final redemption, and would often cite how once, when the soul of the founder of Chassidism—Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov—ascended above, he asked the Moshiach when he would arrive and redeem his people. The Moshiach replied: “When your wellsprings flow outwards.” The Rebbe saw the culmination of that idea as not merely bringing the general teachings of Chassidus to the masses, but by bringing the “wellspring” itself, by physically printing a Tanya in every city where even one Jew lives.

Additionally, the Rebbe said, the act of printing such a holy work elevates the entire city in which it’s printed.

In the decades since the Rebbe’s call, about 8,000 editions have been printed (a full list of editions is printed in every Tanya), and new editions are still being printed regularly: from desert towns in Arizona to Guadeloupe, a distant French territory in the eastern Caribbean.

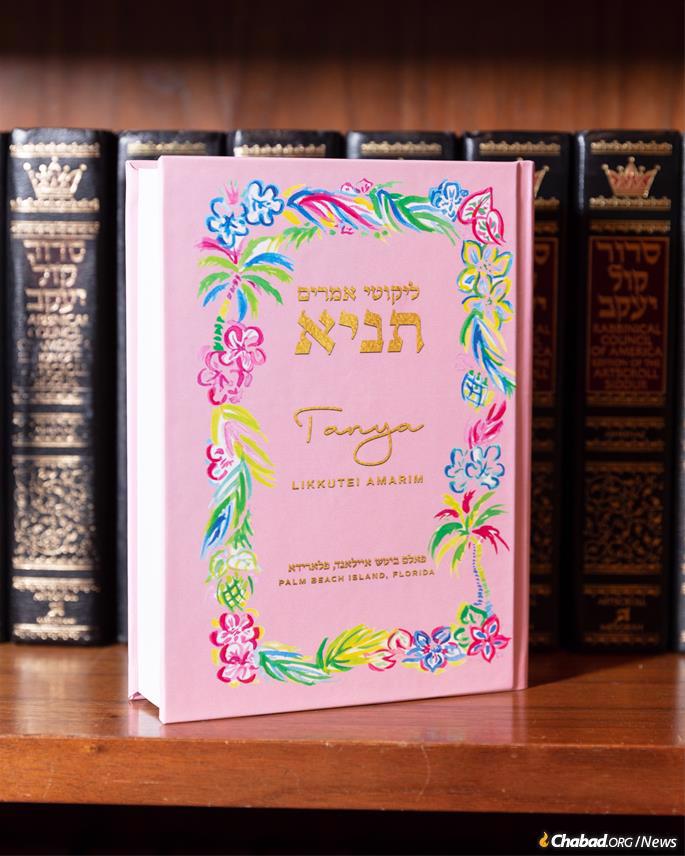

The Palm Beach Tanya

When the Palm Beach Synagogue’s Tanya group heard about the Rebbe’s wish for Tanyas to be printed everywhere, they took for granted that an edition had long ago been published by the large Jewish population on Palm Beach Island. Upon trying to locate a copy, however, they discovered that there had actually never been a local printing. The women contacted Kehot Publication Society, Chabad-Lubavitch’s official publishing arm and the body responsible for publishing all original texts of the Chabad masters, who in turn assigned them an edition number for a first-ever publishing on the island.

The group was determined to publish a beautifully designed edition that followed Kehot’s guidelines. Hindy Krasnianski, an artist and the rabbi’s daughter, poured her creativity into the project; incorporating the local aesthetic and the study group’s feminine flair into the cover design, ensuring that community members not familiar with the Tanya would be intrigued by the mixing of old and new and be drawn to its study.

Upon completion of the expert printing and binding of the beautiful new edition, the group got together to learn from the text and attend a celebratory breakfast to mark the historic community event together with their teacher, Hindy Pruss.

“From beginning to end, this collective endeavor has changed our community,” says Scheiner. “The power of Tanya has uplifted and elevated this beautiful place, a city that once didn’t allow Jews to reside here.”

“It came from the women,” emphasizes Pruss. “Tanya has really become a thing in Palm Beach. Nobody’s recruiting; people just find out about it and make it theirs.”

Providing Insights and Room to Grow for Every Student

Each teacher brings their own style and teaching method to their work and each uses different resources to prepare his or her classes.

Pruss says that after reading through the basic text, she listens to master teacher Rabbi Yehoshua B. Gordon’s classes on Chabad.org, followed by Rabbi Aron Moss’s video classes on Chabad.org, and then finally summarizes key ideas from the chapter using Sparks of Tanya. “Throughout the week, I gather insight and inspiration from a series of writings, and then I fold in some stories connected to the themes we’re pursuing in the class,” she explains.

While Pruss’s classes go through the entire Tanya in order of the chapters, some teachers choose to focus on specific sections they feel their audience will connect to more.

Slavutin says he doesn’t cover the entire Tanya in his classes, which he also delivers over the phone to the homebound, but selects chapters and topics that resonated with him when he began to study Tanya. His primary resource in preparing his classes is the bestselling Lessons in Tanya, and he also uses the more recent commentary of Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, HaTanya HaMevuar (available in English as The Steinsaltz Tanya), as well as Rabbi Chaim Miller’s The Practical Tanya.

In his yeshivah classes, Burg leads his students through the first section of Tanya, which he delves into using the extraordinarily deep yet crystal-clear explanations of famed Chassidic scholar Rabbi Yoel Kahn, accompanied by the acclaimed Hebrew series Chassidut Mevueret. (A pilot English-language edition of Chapter 32 was recently released.)

Burg also teaches select Tanya classes in several women’s seminaries in Jerusalem, including Tomer Devorah and the Bnot Torah Institute. His Tanya classes at the NCSY Kollel are a big draw as well.

He says the first chapters completely change one’s perspective. The Alter Rebbe’s careful textual analysis of the age-old Talmudic terms of tzaddik, rasha and beinoni (“righteous,” “wicked” and “average” people) turns their traditional meanings on their heads.

In the classical sense, using only a “borrowed” meaning of the words, a tzaddik means simply a good, virtuous person (who certainly also has times of shortcoming), a beinoni is one whose deeds are equally distributed—half good deeds, half sinful actions—and the rasha is the condemned, wicked sinner. The Alter Rebbe teaches that the tzaddik has no negative inclination, and there are only a select few throughout the generations. The beinoni is reframed as equivalent to or even higher than what many consider a tzaddik to be: an individual who may have negative urges and desires, but doesn’t act on them, i.e., never commits sin. And, finally, the rasha emerges as one who slips up, even if only occasionally.

“There’s an undercurrent of infinite compassion for the rasha in Tanya,” notes Burg. “For a young man who’s being told he needs to have everything under control, that’s huge. It’s a relief—I’m not expected to be a perfect tzaddik. Having human urges and desires is natural, and I have to utilize the tools I’ve been given to work on my conduct.”

“Kids today are looking for meaning; they’re rejecting a passionless Yiddishkeit,” says Burg. “They want to know why they’re doing what they do. Chassidut gives them that insight. There’s nihilism today—who wants to sit on their phone and be miserable? They want to have meaning.”

“The beauty of Tanya is that it gives you tremendous insight into our relationship with G‑d and the Torah,” says Slavutin. “Learning the other parts of Torah after having studied Tanya was like coming to the ocean from the desert.” The popularity of Tanya today, he feels, is a response to this generation. “The world is in a state of chaos, and people are looking for an anchor, stability. Tanya gives a sense of peace among the chaos.”

Join the Discussion