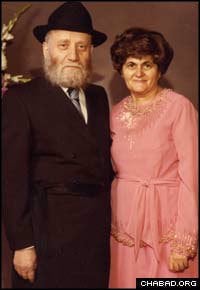

Rabbi Tzvi Yosef Kotlarsky, a Polish-born Chasid who escaped war-torn Europe via Japan and China to ultimately participating in the building of the Chabad-Lubavitch school systems in Montreal and Brooklyn, N.Y., passed away Monday at the age of 91. Known by his Yiddish name Hirschel, the rabbi served as chief administrator of the United Lubavitch Yeshiva in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights section for decades.

Born in a small vacation town in Poland, Kotlarsky grew up in the Kotzk Chasidic home of Yaakov Dovid, a ritual slaughterer, and Nechamah Devorah Kotlarsky. At a young age, Kotlarsky moved with his family to the Lublin district town of Glusk, a relatively bigger location, boasting 125 families.

The young Hirschel first learned in the local grade school before traveling to Warsaw to study in the Tomchei Tmimim Lubavitch yeshiva there. By the time he was 14, he returned home to immerse himself in Jewish texts with his brother.

“I decided with my brother that within a year, we would complete the entire Talmud,” Kotlarsky related in 2006. “We got up at four in the morning and we learned.”

He later enrolled in the Chochmei Lublin Yeshiva headed by Rabbi Meir Shapiro, a scholar Kotlarsky remembered as giving “brilliant lectures.” On the advice of the Kotsker Rebbe, Kotlarsky continued his studies at the Lubavitch yeshiva in Otwock, some 25 kilometers from Warsaw. Out of 180 boys who registered at the school that year, only Kotlarsky and seven others were accepted to the respected academy.

“Thank G‑d, I was selected as one of them,” he said. “If you came in at 2:00 at night, at times, you couldn’t find a place to sit. I remember, I had a set time to learn with a study partner at 4:00 in the morning. We used to get up, go in the woods, sit down there and learn.”

Kosher in the Polish Army

In 1938, Kotlarsky was drafted into the Polish army. Prior to leaving Otwock, he went to a private audience with the Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory.

“The Rebbe told me that G‑d should help that the decree should be nullified,” said Kotlarsky.

The young man’s cavalry division was assigned to a position close to the Russian border. According to Kotlarsky, obtaining kosher food was the most difficult part of his tour. His family sent packages to help him keep nourished.

“I had [daily] a piece of preserved meat with black bread,” said Kotlarsky. Anything else, “they couldn’t send. The other [servicemen] ate in the army kitchen. I did not, because I was not going to eat non-kosher food.”

On Shabbat, Kotlarsky tried to go to the local Jewish community, where he had invitations from some families to eat with them.

There were just 11 other Jewish servicemen in his unit.

The officers “were scared that we would escape to Russia,” he detailed. “So we weren’t directly near the border. They didn’t trust the Jewish members.”

Three months before the outbreak of World War II, Kotlarsky’s unit was transferred clear across the country to Radomsk, a city near the German border. The Thursday night when the war broke out, “I and another three boys were assigned for duty about a kilometer away [from] the German border.”

The Germans bombed the entire area, knowing it to hold an armory.

“They bombed it together with the whole village,” said Kotlarsky.

Fractured, the unit disbanded. Kotlarsky never found them.

He saw in his saving the fulfillment of the Rebbe’s blessing to him earlier.

“When the war broke out,” he said, “I got freed altogether. I was supposed to serve a year and a half, and I didn’t finish my turn. The [unit] just fell apart.”

Escaping War-Torn Europe

During the first month of the war, Kotlarsky, like many others, was confused as to what his next move should be. He first thought of going to Romania and from there, making his way to the Holy Land. With that option impossible, he traveled from city to city. He even traded his army uniform for regular clothes so that he wouldn’t stand out as a target.

In Lemburg, he met a fellow student from the yeshiva, who told him that others were traveling to Vilna in Lithuania.

“I joined those heading out to Vilna,” related Kotlarsky. “It took a very long time, but we finally made it.”

In Vilna, Kotlarsky took a leadership position at the local Lubavitch school. The staff and students were among thousands who received emergency transit visas from the benevolent Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul who risked his own career to save Jewish refugees. With the visas in hand, some 37 students were able to travel through Russia for a hefty price and sail from the eastern port of Vladivostok to Japan.

Although the United States originally promised them visas, when the group arrived in Japan, American diplomats refused to issue the documents. Instead, Kotlarsky and eight others were granted permission to immigrate to Canada after their trans-Pacific journey from Shanghai, China, to S. Francisco.

From California, the nine were escorted by an immigration officer to Chicago and from there, to Montreal. While in Chicago, Rabbi Yisroel Jacobson, one of the leading Lubavitch figures in the United States, greeted them with a message from the Sixth Rebbe, who in 1940, successfully made his way to New York.

Jacobson “came up on the train,” recalled Kotlarsky. “He told us that we’re [going to Montreal] to establish a yeshiva. As soon as we [arrived], as soon as slept the night, we started a yeshiva.”

In Montreal, Kotlarsy was recruited to direct the Kerem Yisroel Talmud Torah, a local program to teach Jewish children in the afternoon. While at first, some 15 children took part in the initiative, by the first year, roughly 150 were enrolled. It later grew to 500 children, many of whom then transferred to learn in Jewish schools full time.

In his few years in the city, Kotlarsky also spearheaded the construction of a Jewish ritual bath.

The Force Behind the Buildings

In 1946, Kotlarsky made his first trip to New York, for the holiday of Passover. At the encouragement of the Sixth Rebbe, Kotlarsky accepted a position at the United Lubavitch Yeshiva, thus facilitating his immigration to the United States. In New York, Jacobson also introduced Kotlarsky to his future wife, Goldie Shimelman.

On the Shabbat before the wedding, the future Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory – who was also a son-in-law of the Sixth Rebbe – spoke at the communal meal following synagogue services. As he did for other brides and grooms, he expounded on the names at hand: Golda and Hirschel.

“Those talks were remarkable,” said Kotlarsky. “The Rebbe would connect the individual’s names to the occasion. For every single person, he had something to say. It did not matter which name.”

In Brooklyn, Kotlarsky served as the chief administrator of the United Lubavitch Yeshiva for some 50 years, humbly directing the building of its two major campuses in the Flatbush and Crown Heights sections. He also supervised the purchases of additional buildings.

“He headed the construction in its entirety,” said Rabbi Yosef Wineberg, who was the vice-chairman of the school. “He did it without making a fuss. He did what he needed to do.”

Today, some 1,500 students learn and live in those buildings. Many thousands more learn in Lubavitch schools around the world.

Even after his wife passed away 18 years ago, Kotlarsky continued at his post.

“The Rebbe wanted him to continue to work in the yeshiva and not to stop his daily routine,” said Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky, vice chairman of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, the educational arm of Chabad-Lubavitch.

A Love for G‑d and Torah

The Kotlarsky home was known for its scholarship and devotion to G‑d and His Torah.

“We used to wake up in the morning,” said Kotlarsky’s daughter, Freidel Hershkowitz, “and he would be learning the Talmud at the dining room table by himself, or with one of the kids.”

The father was always available to learn with anyone who wanted or needed assistance.

“There were many parents who didn’t have a background in Jewish education in the community,” said Hershkowitz. “My father always had the time to assist them with their kids’ homework.”

“He had all the patience in the world,” said the daughter.

“Whenever I met him,” echoed Rabbi Hirschel Fox, a close friend “we would never sit and chit-chat. Rather, we would sit and learn.”

Even when he was ill and in extreme pain, undergoing various medical ordeals over the course of 30 years, “we learned deep discourses in Chasidic philosophy,” said Wineberg. “He forgot about all his pain and learned as if he wasn’t even sick.”

During his father’s stays in the hospital, sometimes in the intensive care unit, Moshe Kotlarsky would report to the Rebbe about his conditions. The Rebbe gave various instructions, from keeping a charity box in Kotlarsky’s room, to gathering a quorum of ten men for High Holiday prayer services at his bedside.

“In 1992, my father was sick over the holiday of Sukkot,” remembered Moshe Kotlarsky “The Rebbe stood that day in the sukkah while thousands of Jews filed by to make a blessing on the Four Species, the lulav and etrog.

“On the way down to prayers,” he continued, “on the top of the staircase, the Rebbe looked around and when he found me, he turned around and asked me how my father was doing.”

Rabbi Mendel Kotlarsky said that his father refused to let his illness take over his life.

“He ignored his excruciating pain,” said the son, especially “when it came to him compromising his daily prayers or Torah learning.”

Once in the synagogue, he passed out and fell off his chair. Mendel Kotlarsky immediately called the medics, but when they arrived, the elderly man was already deep in prayer. When they tried to convince him to go to the hospital, he stated that he would rather wait until after he had completed his prayers.

At the age of 89, Kotlarsky told his interviewer: “I am still around and kicking! I cannot complain, nothing.”

“He knew every one of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren by name, and it is not a small amount,” said daughter Esti Wilshansky. “He beamed every time they would come to his home and enjoyed his time learning the Talmud with them.”

Commenting on the arc of his life, Kotlarsky recently pointed to a picture of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren and told his son-in-law, Mendel Hershkop: “Jacob says in Genesis, ‘For with my staff I crossed this Jordan.’ You see, I did not even have a staff, and look what I have today.”

Rabbi Tzvi Yosef (Hirschel) Kotlarsky passed away Monday, a week after his 91st birthday, and was buried the same day before sunset. He is survived by his children, Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky, Rabbi Mendel Kotlarksy, Chumie Hershkop, Esti Wilshansky, Suri Perlman, Freidel Hershkowitz, and Chani Shemtov; and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Many of his descendants serve as Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries around the world.

Join the Discussion