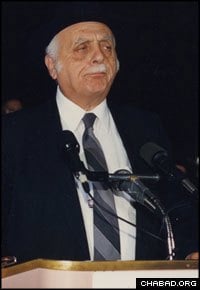

Rabbi David B. Hollander, a longtime orator who worked tirelessly to defend Jewish faith and practice, passed away at the age of 96 last month, having never retired from the pulpit. Over the course of his career, he served as a president of the Rabbinical Council of America and an executive committee member of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis.

Born in Hungary to Rabbi Yonasan Binyamin and Rachel Hollander in 1913, the young Hollander came to New York at the age of 13 after his father took up a position in the city as a pulpit rabbi. He studied in the Torah Vadaath and Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan religious institutions, but also attended Brooklyn Law School while continuing his rabbinical studies.

In 1942, Hollander followed his father into the rabbinate, receiving his ordination a short time before accepting a position at one of the largest congregations at the time: the Mount Eden Jewish Center in the Bronx. It was said that under his leadership, all of the 700 seats in the synagogue’s main sanctuary were full five minutes after the beginning of the 9 a.m. Saturday morning service; by 9:30, the doors had to be closed.

“He was a typical English-speaking maggid,” said Rabbi Fabian Schoenfeld, the rabbi of Young Israel of Kew Garden Hills and a past president of the Rabbinical Council of America, using an old-world term reserved for inspirational orators, “an outstanding lecturer.”

In 1948, he married his wife Fay, who was a full partner in his life’s work.

Ira Nosenchuk, who attended many of Hollander’s addresses over the course of 30 years, said that the rabbi’s talks were unique: “He was able to understand current events … and link them to that week’s Torah reading and our everyday life.”

Hollander remained at the Mount Eden Jewish Center until its closing in 1980 due to the migration of Jews to other areas of the city. His next pulpit, which he held until his passing, was at the Hebrew Alliance Congregation in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn.

Travels Abroad

But while the rabbi’s inspirational style of teaching Torah earned him a reputation in the United States, his devotion to strengthening Jewish practice would quickly take him abroad. During a visit to Washington, D.C., in 1955, Hollander decided to approach the Russian Embassy to announce his wish to visit Jewish communities in the Soviet Union.

“I said to myself, we have to break this idea that there can be no contact between us and the Jews in the Soviet Union,” Hollander related in a recent interview.

He arrived at the embassy fully expecting to be thrown out. But after he told one of the staff members that he wanted to speak with someone about organizing a rabbinical delegation to Russia, an official instructed him to fill out a questionnaire and detail his plan.

“They expressed great interest in my visit,” said the rabbi.

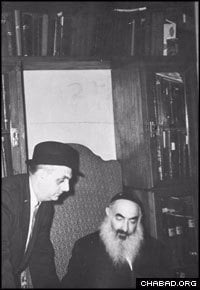

He eventually received permission to travel, and organized a delegation from the Rabbinical Council of America to accompany him. Prior to setting out on his journey, he met with the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, who advised him to be careful about what he said in public.

“You have an American passport in your pocket, so you’re okay,” Hollander remembered the Rebbe telling him. “But the Jews in Russia don’t have that, and they may pay the price of what you may say publicly.”

When he met with people in synagogues sanctioned by the state, he could clearly identify Russian agents attempting to blend in.

“They were supposed to report on everything that was said and done,” he related in an interview with Yechiel Cagen, director of the Jewish Educational Media’s oral history project documenting the life of the Rebbe.

Mindful that he couldn’t overtly encourage the local Jewish population to strengthen their religious practices, Hollander concealed his messages. He once spoke about the biblical story of Balaam, the evil prophet who rose early in the morning on a mission to harm the Jewish nation during its sojourn in the desert.

Hollander focused on a commentary on one of the story’s verses: “You evil person,” the commentary says of Balaam, “the wise man [Abraham] has already preceded you. He rose early in the morning on a mission from G‑d, the binding of Isaac. In that merit, the Jews will not be harmed by you.”

“I thought it was a rather diplomatic way to tell the Jews to have hope,” said Hollander.

On another occasion, a congregant approached Hollander as he exited the synagogue one Shabbat. With a clever twinkle in his eyes, the man said: “Rabbi, you just violated the Shabbat.”

An astounded Hollander stared at the man. How could it have been possible to violate Shabbat, he thought.

Referring to the prohibition of lighting a fire on the holy day, the man told Hollander that he violated the Shabbat with his talk: “You lit a fire within us,” said the man.

During his visit, he met countless Chabad-Lubavitch disciples who ran an underground system of Jewish schools and Torah classes. And although he was warned not to, he went to a Talmud class, finding it in a home that served as one of the locations of a Lubavitch school that moved from place to place on a daily basis.

Upon his return, Hollander went back to the Rebbe to report on the trip, relaying many messages from the Chabad-Lubavitch community in the Soviet Union. The rabbi traveled to Russia an additional six times, taking great pride in a series of accomplishments, including successfully petitioning the Soviet government to publish hundreds of prayer books. Before each visit, Hollander conferred with the Rebbe.

“The Rebbe knew Russia better than anyone else,” he stated.

An Influence on Many

Back in the States, Hollander became a sought-out lecturer.

“He was definitely a man of integrity, of principle and truth,” said Nosenchuk. “He was a straight talker.

Hollander “understood people very well,” added Nosenchuk. He “understood where people were coming from, whether they were ordinary people or presidents.”

In the 1950s, when Mount Scopus Memorial College – a private Jewish day school in Melbourne – was looking for someone to deliver a lecture on education to the Australian Jewish community, the Rebbe advised the school to fly down Hollander. Through the years, Hollander logged many flights across the globe, delivering speeches not only in Australia, but South Africa as well.

“He fascinated people with the way he spoke,” said Rabbi Mendel Lipskar, executive director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Johannesburg. His talks possessed “tremendous insight and relevance. His views were clear and expressed in a positive way.

“South African Jewry would flock to listen to him,” added Lipskar, “and his presence contributed to Jewish institutions in Johannesburg.”

Rabbis throughout South Africa frequently phoned Hollander for advice before making major sermons.

“I remember,” said Chaim Mandel, a nephew of Hollander, “that the phone would ring constantly every Friday. Rabbis used to call him for ideas for their sermons on the weekly Torah reading.”

On a personal level, said Nosenchuk, Hollander influenced countless others in developing and utilizing their G‑d given talents.

“He encouraged me to not be hesitant in expressing my opinions in writing, or at the lectures we attended together,” he said.

Others drew lessons from the way Hollander lived his daily life, said Mandel. “It was the lessons in integrity – which he taught not merely by word, but primarily by example – that will stay with me.”

A Man of Principles

When the Mount Eden Jewish Center closed, Hollander was owed a large sum for his salary and assorted services. Seeking to repay their beloved rabbi, who had a family to support, the synagogue’s board members decided to sell the building.

But an organization that Hollander was ideologically opposed to offered the only hope of the synagogue being able to repay the rabbi. Knowing that he would not approve of the sale, the board members solicited, and received, approbations from several rabbinical authorities.

True to form, Hollander refused to sanction the transaction.

“Gentleman,” Hollander told the group, “you do not owe me anything.”

Board members exited the room misty-eyed, in awe that the rabbi they came to revere made such a sacrifice.

“He was a man of tremendous principles,” said Schoenfeld of the Young Israel of Kew Garden Hills. “He had no doubts in them, and tried to bring them into practice.”

In his interview with JEM, Hollander told Cagen that it was the Rebbe who encouraged him to unflinchingly guard his principles.

“I [was] simply looking for some kind of a spiritual anchor to hold,” Hollander said of his first meeting with the Rebbe, in the early 1950s.

“I remember the Rebbe’s answer,” he continued. The modern age demanded that everyone be a leader: “I understood that [I] had to rely upon myself, my own understanding, my conscience, and so on.”

His dedication to principle manifested itself in his defense of Torah and Jewish practice.

“He was a person who was steadfast and inflexible,” said Schoenfeld. “He did not care about getting the approval of others.”

Still, Hollander “respected people, no matter where they came from: religious or not religious, important or not important,” said Nosenchuk.

Hollander’s own approach even clashed at times with Chabad-Lubavitch policies, which the rabbi criticized at times as too benevolent toward those whose religious affiliations ran counter to Jewish law.

Eventually, the rabbi came to respect the Rebbe’s approach, if not endorsing it.

“The Rebbe was a man of Truth,” he said once. “I was not a Chassid, and the Rebbe never attempted to make me into a Chassid.”

“Even though many did not agree with him,” said Schoenfeld, “everyone respected him. Everyone heard him and respected his views.”

Little Odessa

Nosenchuk said that he first heard Hollander when the rabbi made an appearance on the controversial talk radio show of Long John Nebel. While many guests of the program pushed the limits of acceptable speech, Nosenchuk was fascinated by Hollander’s lucid answers and thought-provoking ideas.

“He was very articulate,” said Nosenchuk.

When he heard that Hollander was taking up a position at the Hebrew Alliance in Brighton Beach, Nosenchuk started attending services at the synagogue, whose congregants had started migrating south to Miami.

“He gave a fantastic speech every single Shabbat,” said Nosenchuk. But, “there were maybe 100 people coming to the synagogue.”

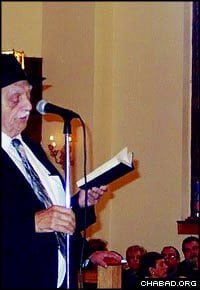

The synagogue, which could seat as many as 1,000 people, was relatively empty, but Hollander devoted the same amount of time to preparing his sermon as he would if he was speaking to a much larger crowd. Even more, “he would give a speech with the enthusiasm and with the feeling as if there were a 1,000 people there,” said Nosenchuk.

Shortly after Hollander’s arrival, the tide of Russian immigration to Brighton Beach swelled, earning the neighborhood the title of “the Little Odessa by the Sea.” A Chabad-Lubavitch institution, Friends of Refugees of Eastern Europe – which goes by its acronym, F.R.E.E. – approached Hollander for permission to use part of his unused synagogue for activities. The rabbi never refused.

In the mid-1980s, Hollander contemplated retiring. During a private audience, he asked the Rebbe for a blessing in returning to private life.

“I am older than you are, and I am taking on additional burdens,” Hollander, in an interview with The Jewish Week, said the Rebbe told him. “By what right do you retire?”

But even as he rededicated himself to his pulpit, most American-born Jews in the area left, causing attendance at his synagogue to dwindle. In the early 1990s, the opportunity for a partnership between the Hebrew Alliance and F.R.E.E. presented itself.

Hollander backed the idea wholeheartedly, according to Nosenchuk, feeling that without the partnership, the Hebrew Alliance’s building would soon not house any synagogue.

As part of the agreement, Hollander continued to run the Hebrew Alliance, which relocated to another building on the property and, later, to the first level of the main synagogue. But he also prepared special sermons for the F.R.E.E. synagogue that took up residence in the building’s main sanctuary.

Today, the building houses an abundance of programs for young kids, teens and adults.

Hollander, who continued to teach daily classes and deliver weekly sermons until his hospitalization, “had a very good relationship with the Russian immigrants,” said Rabbi Herschel Okonov, executive director of F.R.E.E. “He would come to many of the programs and would give lectures only the way he knew to do it.”

“He was a huge motivation for many of our expansions over the years,” added Rabbi Avremel Okonov, associate director of F.R.E.E. of Brighton Beach, who is working with Hollander’s widow on a fitting memorial. “The people in our synagogue are very heartbroken. As every Shabbat passes, everyone is realizing the great loss that our synagogue suffered. Many of our programs would have never happened if not for him.”

Rabbi David B. Hollander was buried in Jerusalem. He is survived by his wife Fay Hollander.

Join the Discussion