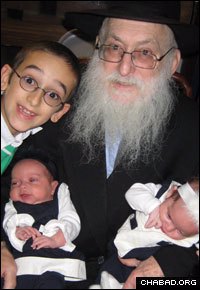

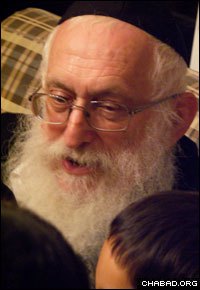

Rabbi Pinchus “Pinny” Krinsky, a ritual slaughterer who tirelessly nurtured and supported a growing Jewish infrastructure in his hometown of Boston, passed away May 4 at the age of 82. Known for both his scholarly achievements and a profound humility, he was among the first to implement modern mass-production techniques to post-slaughter koshering of chickens.

Born in 1927 in suburban Boston to Rabbi Shmaya and Etta Krinsky, he grew up in a home characterized by his parents’ hospitality and activist spirit. In his childhood, Krinsky’s parents even enlarged their kitchen and bought a larger dinette table in order to accommodate throngs of guests.

After the 1940 arrival of the Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yizchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, in New York and the establishment of the central Chabad-Lubavitch yeshiva in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, Krinsky joined his two brothers to learn there. When the Sixth Rebbe’s son-in-law, the future Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, arrived a year later and took the helm of the movement’s educational arm, Krinsky volunteered after his studies to help prepare publications under his editorial guidance.

A story Krinsky frequently shared illustrated the impact that the Rebbe, known then by the acronymic name Ramash, bearing had on the young teenager.

“Once my older sister came to the office where I was working, when the Ramash told me that [she was] waiting for me in the hallway,” Krinsky related in a 1999 interview. “I was hesitant, wanting to finish off my task [before] meeting her. The Ramash, seeing that I was taking my time, told me to ‘either bring her a chair to sit on while she waits for you, or invite her in to have a seat.’ ”

Brighton, Mass., Shmuel Volchek said that Krinsky exemplified the story’s message.

“He had an unbelievable respect for other people,” said Volchek, who looked to Krinsky as a mentor. “He was very understanding of us beginners, and had a huge amount of patience to learn with those whose Jewish educations were minimal.”

Another story that Krinsky told centered on being inspired by scholasticism typified by the Rebbe: Rabbi Nissan Telushkin, rabbi of the Nusach Ari synagogue in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn, had arrived in Crown Heights for the nighttime recitation of the entire book of Psalms during the last intermediate day of Sukkot known as Hoshanah Rabbah. Prior to the beginning of Psalms, Telushkin entered into a scholarly discussion with the future Rebbe that outlasted the congregational recitation. But because many have the custom to not speak during the service, the two scholars would periodically pull thick volumes of Jewish law and the Talmud off the shelves, pointing to relevant passages to continue their discussion without words.

“He would always have a scholarly book open,” Bolchik remembered of Krinsky. “In his home, if he ever had a free second, he would sit and learn. He was very knowledgeable and taught us a lot.”

Innovations and Leadership

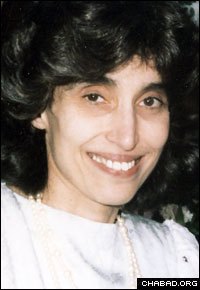

In 1955, Krinsky married Pearl Fleischer, moving across the street from his parents’ home in Dorchester. There, Krinsky assumed communal responsibilities at the local Anshei Lubavitch synagogue.

The Rebbe, in a 1958 letter, guided Krinsky on how best to work with a community whose members were frequently older than him.

Later, he followed his father into kosher slaughtering, opening Menorah Kosher Poultry with his brother. Krinsky, wishing to extract efficiencies out of what was then a manual process of salting chicken carcasses to remove the blood – a necessary step in the preparation of kosher meat – developed an automated system relying on conveyor belts and other machinery. Krinsky’s process, later adopted by all the major kosher slaughterhouses and still in use today, saved producers a considerable amount of money and brought down the cost of kosher chickens for the consumer.

As the Jewish community in Dorchester dwindled, Krinsky moved his growing family to Brighton. There, he and his wife established the Lubavitch Shul in their basement. They later opened the area’s only Jewish ritual bath, which Krisnky built with his own hands under rabbinic supervision. After it was built, he maintained the mikvah, while his wife served as the attendant.

The couple also offered Torah classes and one-on-one study opportunities to Jewish residents of all stripes.

“The thing about the Krinskys was their humility,” said local teacher Shulamis Gutfriend. “They lacked any ego, and were doers in their quiet way.”

Members remembered the synagogue – which the Krinskys later relocated in order to accommodate more people – as possessing a homey atmosphere.

“It was a real cozy and comfortable little [synagogue],” wrote Leslie Seigel. “They made sure to tell us that we were welcome anytime, even if we couldn't afford to pay for dues or High Holiday seats.

“Pearl sat next to me during services and helped me follow along,” she continued. “Many times, they also invited us to eat the afternoon meal with them and their family.”

Krinsky’s home became a haven for many. It was not uncommon for people to move in and stay for months at a time.

“He was everything to me,” said Rabbi Dan Rodkin, director of the Shaloh House Jewish Day School in Brighton. “I lived in one of the rooms in their house. He was my second father. Everything he did was full of dignity, never as if he was doing me a favor.”

“Everyone loved their Shabbat table,” echoed Gutfriend. “Rabbi Krinsky’s stories were beautiful. Many times, when he told a story, he had tears in his eyes.”

Even as they got older, the Krinskys, whose kosher food store was the only one in the area for many years, didn’t pass on the chance to help out someone in need.

“They would go out at all hours of the day and night as in they were teenagers just to help others, to visit people who needed to talk,” said Gutfriend.

Later on in his life, Krinsky dedicated his efforts to supporting Jewish activities as a full-time Chabad-Lubavitch emissary. But he shunned the title of “rabbi.”

“It was more about the spirituality,” said Tzvi Webb, who as a young man, worked in Krinsky’s poultry company. “I would watch him closely, his work, his prayers and his learning. Those were the most important things to him.”

Surrounded by his children, Krinsky succumbed to a short illness just two weeks after his sister, Chicago Jewish leader Chava “Evelyn” Shusterman, passed away at the age of 89. Even at the late hour, close to 300 people showed up to bid farewell as he was transported to New York for burial at the Old Montefiore Cemetery in Cambria Heights.

Community members said that thousands would have shown up had the funeral been held in Boston.

“He lived his life humbly and unassuming,” said Rodkin, “and his funeral was the same way.”

Rabbi Pinchus Krinsky is survived by his children, Miriam Grossbaum of Melbourne, Australia; Sima Pruss of Brooklyn, N.Y.; Rivkah Altein, activities director of the Chaya Mushka seminary in Montreal; Gittel Krinsky-Vogel of Brighton, Mass.; Rabbi Shmaya Krinsky of Morristown, N.J.; Etta Feigelstock of Pittsburg, Pa.; Rabbi Shalom Ber Krinsky, director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Lithuania; Chanie Serebryanski, co-director of Chabad of South Denver in Colorado; and Rabbi Mendel Krinsky, executive director of the Chabad Jewish Center in Needham, Mass.

Join the Discussion